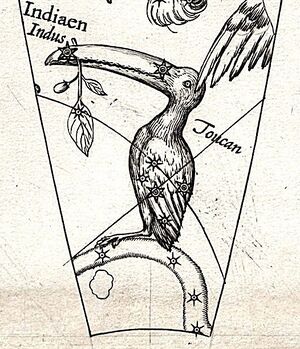

Tucana

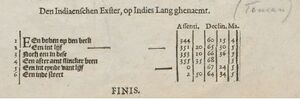

"den Indiaenschen Exster, op Indies Lang ghenaemt" (the Indian Magpie, known as "Lang" in the Indies) was the original Dutch name of the constellation of the bird that is now called "Toucan" (Tucana, Tuc). The constellation was invented by Pieter Dircksz Keyser and Frederik de Houtman on their journey to Indonesia in 1595/6.

Invention & Transformation

The southern star catalog by de Houtman[1] and Keyser was published by de Houtman in 1603 as an appendix to a dictionary of the Malaysian (and other) language(s). This star catalog was written in Dutch (with later translations to French,[2] English[3][4] and Spanish[5]). This printed catalogue of 1603 was made from observations collected by de Houtman on his second voyage (1598-1602) and during the two-year period when he was held as a hostage by the Sultan of Aceh on Northern Sumatra. At that time, de Houtman worked for W.J. Blaeu, a Plancius competitor, who used the data on his celestial globe of 1603.

Before the publication of his star catalogue, de Houtman had shared the data from the first voyage (1595/6) with Petrus Plancius who had actually commissioned this work. Plancius used the data collected by Pieter Dircksz Keyser on the exploration "Eerste Schipvaart" ('de eerste schipvaart op Oost-Indie'); De Houtman may have assisted in making these observations, and as Keyser was buried on the island of Java, de Houtman may also have been the person who personally communicated Keyser’s data to Plancius in 1597, but this is nowhere explicitly stated, it is just assumed because Plancius had worked with this material, and his celestial globe of 1598 already displayed paintings of the newly invented constellations in the south. The images had the labels "Indian" and "Toucan" left and right of the bird, while the left label ("Indian") also referred to the male figure northwest of it. Petrus Plancius' work and/or its copies by W. J. Blaeu served as source for Bayer's Uranometria (1603). Bayer's map of the south pole also displays the image with the label "Toucan" and an extraordinarily long beak.

Lang

During the first half of the 17th century the alternative name 'Lang'[6] was also used on Dutch and French celestial globes and maps.

- celestial globe of Willem Jansz Blaeu dated 1603.

- undated pair of celestial planispheres by an unknown author.

- pair of celestial planispheres by Melchior Tavernier dated 1628.

- pair of celestial planispheres by Antoine de Fer dated 1650.

After c. 1650 the name Lang does not seem to be used anymore on celestial globes and maps.

Species of this bird

The additional phrase in de Houtman's catalog, mentioning that the bird was named "Lang" is occasionally misinterpreted to be the cause for this depiction, implying that "Lang" in Dutch means "long" and refers to the beak. In de Houtman's days the Dutch word for long was usually spelled as "lanck", so "Lang" is actually the name of the bird in the Malay language (cf. Maass 1926)[7]. According to the Malay-English Dictionary (1901), it is the a generic term for birds of prey such as hawks, kites, falcons and eagles.

The hornbill's beak and crown start off white, but they may gradually turn orange and red because the hornbill rubs its beak against a gland. Although hornbills' favorite food is fig leaves, they also commonly eat insects, mice, lizards, and small birds.

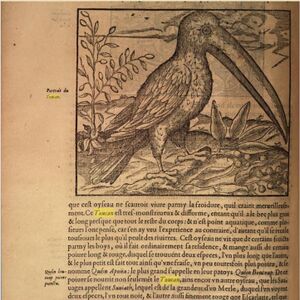

It looks like illustrations of Toucans from Brazil were already in books in the late 1500s, see books by André Thevet (e.g. Thevat 1558, Thevat 1575), so one could imagine in late 16th century Dutch ports there was access to books with an illustration of the South American Toucan, even if they never saw the hornbill endemic to Africa, India, Indonesia.

Indigenous importance

In the Indonesian language, the bird is called "Burung Enggang" or "Burung Rangkong." Renowned on the island of Borneo, this human-friendly hornbill is closely associated with the Dayak people. In Dayak philosophy, the bird holds great significance and is deeply embedded in their culture and local wisdom. The hornbill symbolises the close connection of the Indonesian people to their natural surroundings. Its entire body represents the greatness and glory of the tribe, symbolising peace and unity, with its thick wings denoting a leader who always protects his people. The long tail is viewed as a sign of the prosperity of the Dayak people. Moreover, the hornbill serves as an example of family life in the community, teaching them always to love their partners and raise their children to become independent and mature Dayaks.

Image description here. more information in Indonesian. 1. Julang Sulawesi (Rhyticeros cassidix), conservation status: vulnerable 2. Kangkareng Sulawesi (Anthracoceros malayanus), Conservation status: near threatened 3. Julang Sumba (Rhyticeros everetti), conservation status: vulnerable 4. Enggang Klihingan (Anorrhinus galeritus), conservation status: low risk 5. Julang Emas (Rhyticeros undulatus), conservation status: low risk 6. Enggang Cula (Buceros rhinoceros), Conservation status: near threatened 7. Kangkareng Hitam (Anthracoceros malayanus), Conservation status: near threatened 8. Kangkareng Perut-putih (Anthracoceros albirostris), conservation status: low risk 9. Rangkong Gading (Rhinoplax vigil), conservation status: critical 10. Julang Irian (Rhyticeros plicatus), conservation status: low risk 11. Enggang Jambul (Berenicornis comatus), Conservation status: near threatened 12. Enggang Papan (Buceros bicornis), Conservation status: near threatened 13. Julang Jambul-Hitam (Rhabdotorrhinus corrugatus), Conservation status: near threatened

Mythology

A Dayak story from Kalimantan reports that hornbills are the incarnation of the Bird Commander. Panglima Burung is a figure who lives in the mountains of inland Kalimantan and has a magical form and will only be present during war. In general, this bird is considered sacred and is not allowed to be hunted or eaten. Even today, the government protects this species by law.

Possible origins of the interpretation of a Toucan

Toucans are not home to the East Indies and Malaysia. Ridpath suggests that the inventor of this constellation was actually Pieter Keyser who had not survived the expedition to the East Indies but had previously visited South America. Hoffmann (2021, 108) considers an image or sculpture of the bird enough to confuse naming. Thus, Plancius and de Houtman would also be possible inventors because baroque ‘wunderkamers’ could certainly have played a mediating role here. Rob van Gent adds that is not necessary that Keyser, de Houtman or Plancius actually saw a live (or dead) toucan as they are bound to descriptions and depictions of the bird in 16th-century travel literature: in particular Plancius would surely have been familiar with these.

With the above mentioned facts on the significance of hornbills in the Indonesian Dayak culture, it appears even more likely that de Houtman (with or without Keyser) named the constellation of the "Indiaenische Exster" (in Dutch) after the hornbill. As the biological differences between hornbills and toucans were likely unknown, the name of the constellation might simply be a confusion caused by the lack of biological knowledge.

Versions in early modern celestial maps

Tucana labelled "Lang" on an anonymous planisphere of the southern sky in the Bodel Nijenhuis Collection of the Leiden University Library (more information).

Tucana labelled "Lang" on Melchior Tavernier's celestial planisphere of the southern sky dated 1628 (Gallica).

Modern Star Name

- "Exster" is proposed as name for the main star of the modern IAU-constellation of Tucana (alf Tuc).

- "Lang" is proposed as name for beta Tuc.

(or vice versa?)

References

- Ian Ridpath, Star Tales. website

- ↑ Frederik de Houtman (1603) Star Catalogue concerning the Indian Magpie

- ↑ Marre, Aristide, “Catalogue des étoiles circumpolaires australes observées dans l'Ile de Sumatra”, Bulletin sciences mathématiques et astronomiques, 1 (1881), 336–352 [ADS link].

- ↑ Knobel, Edward Ball, “On Frederick de Houtman's catalogue of southern stars, and the origin of the southern constellations”, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 77 (1917), 414–432 [doi link / ADS link].

- ↑ Knobel, Edward Ball, “Note on the paper 'On Frederick de Houtman's catalogue of southern stars, and the origin of the southern constellations' ", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 77 (1917), 580 [doi link / ADS link].

- ↑ Selga, Miguel, "Un catálogo antiguo de estrellas australes", Revista de la Sociedad Astronómica de España y América, 8 (1918), 84-90 & 9 (1919), 11, 44-46 & 62-63 [online link(?)].

- ↑ Not to be confused with the modern Dutch word for the adjective "long". In late 16th- and 17th-century Dutch sources this was commonly written as "lanck" or 'langh".

- ↑ Maass, Alfred, "Sternkunde und Sterndeuterei im malaiischen Archipel", Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 64 (1924), 1-172 & 347-459 [online link], with a "Nachtrag", 66 (1926), 618-670 [online link].