Camelopardalis: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (6 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

==Etymology and History== |

==Etymology and History== |

||

Camelopardalis was invented in 1612 by Petrus Plancius and represents a giraffe. The constellation’s name is Greek ''Καμηλοπάρδαλις,'' which was adopted by ancient authors into Latin ''Camelopardalis'' (e.g. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia VIII, 69), derived from the words for “camel” and “leopard”, reflecting an animal suited to hot climates like a camel, yet marked with spots like a leopard. |

Camelopardalis was invented in 1612 by Petrus Plancius and represents a giraffe. The constellation’s name is Greek ''Καμηλοπάρδαλις,'' which was adopted by ancient authors into Latin ''Camelopardalis'' (e.g. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia VIII, 69), derived from the words for “camel” (κάμηλος, kamelos) and “leopard”, reflecting an animal suited to hot climates like a camel, yet marked with spots like a leopard. Thus, actually, the Latin word Camelopardalis is a transcription of the Greek word for giraffe and literally means “spotted camel,” but this was probably already forgotten in Roman times. |

||

Incidentally, the fact that it is a Greek loanword explains the ending -is instead of -us in the nominative case of the name. It also explains why the nominative and genitive cases are the same in Latin. |

|||

In the 19th century, Bode wrote “der Kameelopard,” which in German is more reminiscent of spotted big cats such as leopards (“spotted lions”) or cheetahs. However, he also means a giraffe and only refers to the alternative interpretation in the text. The correct term “Cameloparalis” used by Delporte<ref>Delporte, Eugène, ''Délimitation scientifique des constellations (tables et cartes)'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1930) [[https://historiadelaastronomia.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/delporte.pdf online link]] -- published on behalf of the International Research Council of the International Astronomical Union</ref> for the IAU is sometimes confusing<ref name=":0" />, because the Greek loanword in Latin also led to the (misleading) Latin variants Camelopardus and Camelopardalus. The original Greek form comes from “pardalis” (spotted) as an adjective to “kamelos” (camel). |

In the 19th century, Bode wrote “der Kameelopard,” which in German is more reminiscent of spotted big cats such as leopards (“spotted lions”) or cheetahs. However, he also means a giraffe and only refers to the alternative interpretation in the text. The correct term “Cameloparalis” used by Delporte<ref>Delporte, Eugène, ''Délimitation scientifique des constellations (tables et cartes)'' (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1930) [[https://historiadelaastronomia.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/delporte.pdf online link]] -- published on behalf of the International Research Council of the International Astronomical Union</ref> for the IAU is sometimes confusing<ref name=":0" />, because the Greek loanword in Latin also led to the (misleading) Latin variants Camelopardus and Camelopardalus. The original Greek form comes from “pardalis” (spotted) as an adjective to “kamelos” (camel). |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

'''Camelopardalis''', ''Καμηλοπάρδαλις'', in Italian ''Giraffa'', the giraffe. An animal the height of a camel, the colour of a panther, and the feet of an ox. It is formed from faint stars near the Arctic Pole, between Cassiopeia and Auriga, as established by more recent astronomers. ''Let it be to me the camel of Rebecca, with which she journeyed with Abraham’s servant to Isaac.'' (Genesis 24:61, 65) (translation: Doris Vickers)</blockquote> |

'''Camelopardalis''', ''Καμηλοπάρδαλις'', in Italian ''Giraffa'', the giraffe. An animal the height of a camel, the colour of a panther, and the feet of an ox. It is formed from faint stars near the Arctic Pole, between Cassiopeia and Auriga, as established by more recent astronomers. ''Let it be to me the camel of Rebecca, with which she journeyed with Abraham’s servant to Isaac.'' (Genesis 24:61, 65) (translation: Doris Vickers)</blockquote> |

||

===== Bode (1782) ===== |

|||

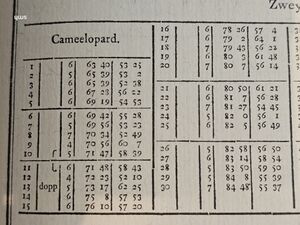

[[File:CamelopardalisTab Bode1782.jpg|thumb|Bode (1782) star catalog for "Cameelopard", the Giraffe.]] |

|||

Bode, in his popular book 1782 even gives little star catalogues per constellation. For Camelopardalis, the third edition of this book (1803) has 30 stars, the brightest two have 4 mag. |

|||

=== Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation === |

=== Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation === |

||

<gallery> |

<gallery> |

||

File:Cam Plancius1612.png|Cam on the Plancius (1612) Globe. |

File:Cam Plancius1612.png|Cam on the Plancius (1612) Globe. |

||

File:Cam Habrecht1621.png|Cam in Habrecht (1628). |

File:Cam Habrecht1621.png|Cam in Habrecht (1628)<ref>Isaac Habrecht, ''Planiglobium Coeleste, et Terrestre. Sive, Globus Coelestis'', 1628.</ref>. |

||

File:Camelopardalis Coronelli1688.png|Cam on the Coronelli (1688) Globe, see [https://homepage.univie.ac.at/georg.zotti/virtual_globes/index.html Zotti's Globe Gallery] |

File:Camelopardalis Coronelli1688.png|Cam on the Coronelli (1688) Globe, see [https://homepage.univie.ac.at/georg.zotti/virtual_globes/index.html Zotti's Globe Gallery] |

||

File:Cam Hevel.png|Cam in Hevelius (1690). |

File:Cam Hevel.png|Cam in Hevelius (1690). |

||

File:Cam Flamsteed 1729.png|Cam in Flamsteed (1729). |

File:Cam Flamsteed 1729.png|Cam in Flamsteed (1729). |

||

File:Cam Bode1782 hi.jpg|Cam in Bode (1782) |

|||

File:Cam Cassini1792.png|Cam on the Cassini (1792) Globe, see [https://homepage.univie.ac.at/georg.zotti/virtual_globes/index.html Zotti's Globe Gallery] |

File:Cam Cassini1792.png|Cam on the Cassini (1792) Globe, see [https://homepage.univie.ac.at/georg.zotti/virtual_globes/index.html Zotti's Globe Gallery] |

||

File:Sidney Hall - Urania's Mirror - Camelopardalis, Tarandus and Custos Messium.jpg|Hall (1825) Camelopardalis |

File:Sidney Hall - Urania's Mirror - Camelopardalis, Tarandus and Custos Messium.jpg|Hall (1825) Camelopardalis |

||

File:Cam Simon1894.png|Cam in Simon (1894) |

|||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

| Line 55: | Line 61: | ||

[[Category:Eurasia]] [[Category:Constellation]] [[Category:Modern]] |

[[Category:Eurasia]] [[Category:Constellation]] [[Category:Modern]] |

||

[[Category:88 IAU-Constellations]] [[Category:European]][[Category: |

[[Category:88 IAU-Constellations]] [[Category:European]][[Category:Cam ]] |

||

<references /> |

<references /> |

||

Latest revision as of 11:50, 13 November 2025

One of the 88 IAU constellations. Plancius (1612) meant and drew the Latin giraffe and not the camel, but the strange word was sometimes misunderstood by other astronomers as camel or as panther.[1] So until the constellations were canonised by the IAU, there were two interpretations of this animal.

Etymology and History

Camelopardalis was invented in 1612 by Petrus Plancius and represents a giraffe. The constellation’s name is Greek Καμηλοπάρδαλις, which was adopted by ancient authors into Latin Camelopardalis (e.g. Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia VIII, 69), derived from the words for “camel” (κάμηλος, kamelos) and “leopard”, reflecting an animal suited to hot climates like a camel, yet marked with spots like a leopard. Thus, actually, the Latin word Camelopardalis is a transcription of the Greek word for giraffe and literally means “spotted camel,” but this was probably already forgotten in Roman times.

Incidentally, the fact that it is a Greek loanword explains the ending -is instead of -us in the nominative case of the name. It also explains why the nominative and genitive cases are the same in Latin.

In the 19th century, Bode wrote “der Kameelopard,” which in German is more reminiscent of spotted big cats such as leopards (“spotted lions”) or cheetahs. However, he also means a giraffe and only refers to the alternative interpretation in the text. The correct term “Cameloparalis” used by Delporte[2] for the IAU is sometimes confusing[1], because the Greek loanword in Latin also led to the (misleading) Latin variants Camelopardus and Camelopardalus. The original Greek form comes from “pardalis” (spotted) as an adjective to “kamelos” (camel).

Origin of Constellation

Although it is a relatively large constellation located in the circumpolar region, which is always visible, no figure was defined here in ancient times. The area between Cassiopeia, Perseus, and the Big Dipper was constellation-free. In the first generations after the introduction of the telescope for observing the sky, some astronomers had begun to establish a “new astronomy” and accept new constellations. The Dutch globe maker Petrus Plancius had already defined new constellations in the southern sky before 1600 and later began to fill the constellation-free areas in the northern sky with figures. Plancius had suggested the name Camelopardalis for this empty area in 1612.

Petrus Plancius (...)

In 1612 (or possibly 1613), Petrus Plancius introduced eight new constellations on a 26.5-centimeter celestial globe published in Amsterdam by Pieter van der Keere. These were: Apes (the Bee), Camelopardalis (the Giraffe), Cancer Minor (the Small Crab), Euphrates Fluvius et Tigris Fluvius (the Rivers Euphrates and Tigris), Gallus (the Cock), Jordanis Fluvius (the River Jordan), Monoceros (the Unicorn), and Sagitta Australis (the Southern Arrow).

Jacob Bartsch (1600-1632)

In 1624, Bartsch published Usus astronomicus planisphaerii stellati[3], a book of star charts that included several new constellations first proposed around 1613 by the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius. Among these was Camelopardalis, the constellation representing a giraffe, which Bartsch depicted on his charts based on Plancius’s celestial globe created by Pieter van den Keere.

Bartsch's description of the constellation in Usus astronomicus planisphaerii stellati reads:

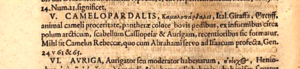

V. CAMELOPARDALIS, Καμηλοπάρδαλις, Ital. Giraffa, Greyff, animal cameli proceritate, pantherae colore, bovis pedibus: ex informibus circa polum arcticum, iis stellulis Cassiopeiae & Aurigam, recentioribus sic formatur. Mihi sit Camelus Rebeccae, quo cum Abrahami servo ad Isacum profecta. Gen. 24. v. 61 & 65[4].

Camelopardalis, Καμηλοπάρδαλις, in Italian Giraffa, the giraffe. An animal the height of a camel, the colour of a panther, and the feet of an ox. It is formed from faint stars near the Arctic Pole, between Cassiopeia and Auriga, as established by more recent astronomers. Let it be to me the camel of Rebecca, with which she journeyed with Abraham’s servant to Isaac. (Genesis 24:61, 65) (translation: Doris Vickers)

Bode (1782)

Bode, in his popular book 1782 even gives little star catalogues per constellation. For Camelopardalis, the third edition of this book (1803) has 30 stars, the brightest two have 4 mag.

Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation

Cam in Habrecht (1628)[5].

Cam on the Coronelli (1688) Globe, see Zotti's Globe Gallery

Cam on the Cassini (1792) Globe, see Zotti's Globe Gallery

Mythology / Religion

The mythological interpretation of this European constellation does not lie in Greek culture, but rather in contemporary Christian culture. Confusingly, it refers to the (incorrect) reading of the word as camel instead of giraffe. It is said to have been the mount on which the Old Testament character Rebekah was brought to her bridegroom.

In the Book of Genesis in the Bible and in the Talmud, the various tribes and peoples are personified and their connections prefigured. According to this story, old Abraham sent a servant to the Arameans to find a wife for his son Isaac. The selection criterion was godliness, and Rebekah had demonstrated this by not only giving the servant a drink at his request, but also his camels. So he asked for her hand for Isaac and brought the caring woman to Canaan.

Normally, men walk alongside the camels and guide the caravan, because a camel will simply stop if a rein or strap to the next animal breaks. Riding is reserved for women.

Weblinks

References

- References (general)

- References (medieval)

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Morgan, Morris H. ; Agassiz, Alexander ; Pickering, Edward C. (1908). The Constellation Camelopardalis. Harvard College Observatory Circular, vol. 146, pp.1-3

- ↑ Delporte, Eugène, Délimitation scientifique des constellations (tables et cartes) (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1930) [online link] -- published on behalf of the International Research Council of the International Astronomical Union

- ↑ Jacob Bartsch, Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati, Argentoratum (Strasburgo) 1624.

- ↑ Jacob Bartsch, Usus Astronomicus Planisphaerii Stellati, Argentoratum (Strasburgo) 1624, p.81

- ↑ Isaac Habrecht, Planiglobium Coeleste, et Terrestre. Sive, Globus Coelestis, 1628.

![Cam in Habrecht (1628)[5].](/mediawiki/images/thumb/c/cf/Cam_Habrecht1621.png/86px-Cam_Habrecht1621.png)