Wei: Difference between revisions

Boshunyang (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Boshunyang (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE: Wei (尾)}} |

{{DISPLAYTITLE: Wei (尾)}} |

||

[[File:Wei in Stellarium.jpg|thumb|Wei in Stellarium]] |

|||

Wei (尾, “Tail”) is the sixth of the 28 mansions/lodges, representing the tail of the Azure Dragon, the first of the Four Symbols of the Chinese sky. It is among the most ancient constellations in the Chinese celestial tradition and consists of nine stars corresponding to those of modern Scorpius. |

|||

Chinese constellation. |

|||

== Concordance, Etymology, History== |

== Concordance, Etymology, History== |

||

The history of Wei as a constellation can be traced back at least to the seventh century BCE. In the ''Zuo zhuan'' ( Zuo Tradition), the section“Fifth Year of Duke Xi (僖公五年),” it is said: “(Before the army attacked the kindom Guo) A children's rhyme goes, ‘On the dawn of the ''bing'' day, the dragon’s tail is invisible while the Sun conjuncts with Moon. The ranks are all arrayed; seize the banner of Guo…’” (丙之晨,龙尾伏辰。均服振振,取虢之旗). Here, “dragon's tail” refers explicitly to the lodge Wei. The complete sequence of the 28 lodges is inscribed, on the lacquered box unearthed from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (early Warring States period, 5th century BCE), naturally including ''Wei''. |

|||

... |

|||

From the Han dynasty onward, Wei acquired a rich variety of astrological interpretations. In the ''Tianguan shu'' (Book of Heaven Officials) of Sima Qian, it is described as “the Nine Sons of Heaven” or “the ruler and his ministers.” The ''Shishi xingjing'' (Master Shi’s Star Canon) records numerous alternate names such as ''Heavenly Latrine'' (''Tian ce''), ''Heavenly Dog'' (''Tian gou''), and ''Heavenly Rooster'' (''Tian ji''), which likely originated from regional astrological schools or popular naming traditions. However, its most widespread interpretation associated the nine stars with the consorts of the emperor’s inner palace: the first star represented the Empress, while the remaining stars corresponded to the ''furen'' (secondary consorts), ''pin'' (concubines), and ''qie'' (lesser consorts). It was probably on the basis of this symbolic meaning that a new asterism, the ''Divine Palace'' (''Shen gong''), came into being. |

|||

The ''Divine Palace'' was conceived as the “inner chamber where the Emperor and his consort disrobe and find pleasure,” the only domain in this solemn astral empire that alludes to intimacy. It bore variant names such as ''Heavenly Excrement'' (''Tian shi'') and ''Heavenly Nine Rivers'' (''Tian jiu jiang''); the former evidently relates to ''Heavenly Latrine'', one of ''Wei''’s alternate names, possibly reflecting a common cultural source. The ''Divine Palace'' was not recorded in any official astronomical compilations before the eighth century, and it likely existed as an unofficial constellation. By the early 8th centuries CE, however, it had been incorporated into ''Wei'' as an auxiliary asterism. |

|||

The Indian-born imperial astronomer Gautama Siddha (fl. early 8th century), serving at the Tang (618 – 907 CE) court, wrote in the ''Kaiyuan zhanjing'' (''Divination Canon of Kaiyuan Reign, KYZJ'', compiles between 712–718 CE) that the officially used star charts and canons did not include this star, but that he had seen it mentioned in a text entitled ''Gu jing zan'' (“Annotation of Ancient (Star) Canons”). He thus adopted it into the official celestial system. According to the record, this star lies beside the determinative star of ''Wei'', at a distance of one ''cun'' (about 0.1 degree). Such a small value was almost certainly not derived from direct measurement, yet it shows that the star lies very close to the determinative star μ¹ Scorpii, clearly identifying it with μ² Scorpii, though its identification might change in later periods. |

|||

=== Identification of stars === |

=== Identification of stars === |

||

The nine stars forming the principal body of Wei have remained unchanged for more than two millennia, and all researchers are in complete agreement regarding their identification. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+ |

|+Wei |

||

!Star Names or Orders( |

!Star Names or Orders(Qing) |

||

!Indexes |

|||

!Ho PENG YOKE<ref>P.-Y. Ho, “Ancient And Mediaeval Observations of Comets and Novae in Chinese Sources,” ''Vistas in Astronomy'', 5(1962), 127-225.</ref> |

|||

!Yi Shitong<ref>Yi Shitong伊世同. ''Zhongxi Duizhao Hengxing Tubiao''中西对照恒星图表1950. Beijing: Science Press.1981: 56.</ref> |

|||

Based on catalogue in 18th century |

|||

!Pan Nai<ref name=":0">Pan Nai潘鼐. ''Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi''中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 1989. p226.</ref> |

|||

based on Xinyixiangfayao Star Map |

|||

!Pan Nai<ref>Pan Nai潘鼐. ''Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi''中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 2009. p443.</ref> |

|||

based on catalogues in Yuan dynasty |

|||

!SUN X. & J. Kistemaker<ref>Sun Xiaochun. & Kistemaker J. ''The Chinese sky during the Han''. Leiden: Brill. 1997, Pp241-6.</ref> |

|||

Han Dynasty |

|||

!Boshun Yang<ref name=":1">B.-S. Yang杨伯顺, ''Zhongguo Chuantong Hengxing Guance Jingdu ji Xingguan Yanbian Yanjiu'' 中国传统恒星观测精度及星官演变研究 (A Research on the Accuracy of Chinese Traditional Star Observation and the Evolution of Constellations), PhD thesis, (Hefei: University of Science and Technology of China, 2023). 261.</ref> |

|||

before Tang dynasty |

|||

!Boshun Yang<ref name=":1" /> |

|||

Song Jingyou(1034) |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|1st/Determinative Star/Hou(Empress) |

|||

|1st/4th |

|||

|mu<sup>1</sup> Sco |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|2nd/ |

|2nd/Furen |

||

|epsilon Sco |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|3rd/ |

|3rd/Furen |

||

|zeta<sup>2</sup> Sco |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|4th/ |

|4th/Furen |

||

|eta Sco |

|||

|x |

|||

| |

|- |

||

|5th/Pin |

|||

|x |

|||

|sigma Sco |

|||

|x |

|||

| |

|- |

||

|6th/Pin |

|||

|x |

|||

|iota<sup>1</sup> Sco |

|||

|x |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|7th/Pin |

|||

|kappa Sco |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|8th/Qie |

|||

|lambda Sco |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|9th/Qie |

|||

|mu Sco |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

===Maps (Gallery)=== |

===Maps (Gallery)=== |

||

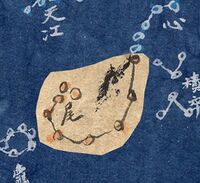

The earliest visual representation of this constellation appears in the mural of the ''28 lodges'' discovered in a Western Han tomb at Xi'an Jiaotong University. However, this depiction uses only one star at the end of the Dragon's tail representing Wei, which clearly reflects an artisan's pictorial convention rather than an astronomer's chart. In contrast, in the Eastern Han mural star map unearthed from a tomb at Jingbian, Shaanxi, Wei and the dragon's tail are closely joined, and all nine stars are shown in full. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ |

|||

!historical map |

|||

!modern identification |

|||

(Yang 2023) |

|||

!same in Stellarium 24.4 |

|||

|- |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|||

Among the earliest realistic star charts—those from the Tang dynasty or earlier, including the ''Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunyajido'', the ''Dunhuang Star Map'', and the ''Geziyuejintu''—''Wei'' is depicted with relative accuracy, though the precision varies among them. Most notable is the ''Suzhou Star Map'', which, unlike other ancient star maps, renders ''Wei'' with greater east–west breadth—an intentional adjustment accounting for the projection distortion near the invisible circle in circular star maps.<gallery widths="200" heights="200" perrow="6" caption="Wei"> |

|||

File:Wei in the Western Han Dynasty Tomb Mural (Xu Gang's Reconstruction Drawing).jpg|Wei in the Western Han Dynasty Tomb Mural |

|||

File:Wei in the Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Mural (Xu Gang's Reconstruction Drawing).jpg|Wei in the Eastern Han Dynasty Tomb Mural |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Wei in Dunhuang Star Map.jpg|Wei in Dunhuang Star Map |

|||

File:Wei in Geziyuejintu.jpg|Wei in ''Geziyuejintu'' |

|||

File:Wei in Suzhou Star Map.jpg|Wei in Suzhou Star Map |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

==Star Name Discussion (IAU) == |

==Star Name Discussion (IAU) == |

||

Latest revision as of 19:59, 6 October 2025

Wei (尾, “Tail”) is the sixth of the 28 mansions/lodges, representing the tail of the Azure Dragon, the first of the Four Symbols of the Chinese sky. It is among the most ancient constellations in the Chinese celestial tradition and consists of nine stars corresponding to those of modern Scorpius.

Concordance, Etymology, History

The history of Wei as a constellation can be traced back at least to the seventh century BCE. In the Zuo zhuan ( Zuo Tradition), the section“Fifth Year of Duke Xi (僖公五年),” it is said: “(Before the army attacked the kindom Guo) A children's rhyme goes, ‘On the dawn of the bing day, the dragon’s tail is invisible while the Sun conjuncts with Moon. The ranks are all arrayed; seize the banner of Guo…’” (丙之晨,龙尾伏辰。均服振振,取虢之旗). Here, “dragon's tail” refers explicitly to the lodge Wei. The complete sequence of the 28 lodges is inscribed, on the lacquered box unearthed from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng (early Warring States period, 5th century BCE), naturally including Wei.

From the Han dynasty onward, Wei acquired a rich variety of astrological interpretations. In the Tianguan shu (Book of Heaven Officials) of Sima Qian, it is described as “the Nine Sons of Heaven” or “the ruler and his ministers.” The Shishi xingjing (Master Shi’s Star Canon) records numerous alternate names such as Heavenly Latrine (Tian ce), Heavenly Dog (Tian gou), and Heavenly Rooster (Tian ji), which likely originated from regional astrological schools or popular naming traditions. However, its most widespread interpretation associated the nine stars with the consorts of the emperor’s inner palace: the first star represented the Empress, while the remaining stars corresponded to the furen (secondary consorts), pin (concubines), and qie (lesser consorts). It was probably on the basis of this symbolic meaning that a new asterism, the Divine Palace (Shen gong), came into being.

The Divine Palace was conceived as the “inner chamber where the Emperor and his consort disrobe and find pleasure,” the only domain in this solemn astral empire that alludes to intimacy. It bore variant names such as Heavenly Excrement (Tian shi) and Heavenly Nine Rivers (Tian jiu jiang); the former evidently relates to Heavenly Latrine, one of Wei’s alternate names, possibly reflecting a common cultural source. The Divine Palace was not recorded in any official astronomical compilations before the eighth century, and it likely existed as an unofficial constellation. By the early 8th centuries CE, however, it had been incorporated into Wei as an auxiliary asterism.

The Indian-born imperial astronomer Gautama Siddha (fl. early 8th century), serving at the Tang (618 – 907 CE) court, wrote in the Kaiyuan zhanjing (Divination Canon of Kaiyuan Reign, KYZJ, compiles between 712–718 CE) that the officially used star charts and canons did not include this star, but that he had seen it mentioned in a text entitled Gu jing zan (“Annotation of Ancient (Star) Canons”). He thus adopted it into the official celestial system. According to the record, this star lies beside the determinative star of Wei, at a distance of one cun (about 0.1 degree). Such a small value was almost certainly not derived from direct measurement, yet it shows that the star lies very close to the determinative star μ¹ Scorpii, clearly identifying it with μ² Scorpii, though its identification might change in later periods.

Identification of stars

The nine stars forming the principal body of Wei have remained unchanged for more than two millennia, and all researchers are in complete agreement regarding their identification.

| Star Names or Orders(Qing) | Indexes |

|---|---|

| 1st/Determinative Star/Hou(Empress) | mu1 Sco |

| 2nd/Furen | epsilon Sco |

| 3rd/Furen | zeta2 Sco |

| 4th/Furen | eta Sco |

| 5th/Pin | sigma Sco |

| 6th/Pin | iota1 Sco |

| 7th/Pin | kappa Sco |

| 8th/Qie | lambda Sco |

| 9th/Qie | mu Sco |

Maps (Gallery)

The earliest visual representation of this constellation appears in the mural of the 28 lodges discovered in a Western Han tomb at Xi'an Jiaotong University. However, this depiction uses only one star at the end of the Dragon's tail representing Wei, which clearly reflects an artisan's pictorial convention rather than an astronomer's chart. In contrast, in the Eastern Han mural star map unearthed from a tomb at Jingbian, Shaanxi, Wei and the dragon's tail are closely joined, and all nine stars are shown in full.

Among the earliest realistic star charts—those from the Tang dynasty or earlier, including the Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunyajido, the Dunhuang Star Map, and the Geziyuejintu—Wei is depicted with relative accuracy, though the precision varies among them. Most notable is the Suzhou Star Map, which, unlike other ancient star maps, renders Wei with greater east–west breadth—an intentional adjustment accounting for the projection distortion near the invisible circle in circular star maps.

- Wei

Star Name Discussion (IAU)

In 202x, the name of the historical constellation "xxx" was suggested to be used for one of the stars in this constellation. ...

Decision: ...

References