Yue: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "Yuè (月) is a name for the Moon of the Earth in China. ==Name Variants and History== What does the term mean, does it always have the same meaning - was it changed over time. ===Name Variants=== ===Dark Spots on the Moon=== In China, there is a huge variety of mythologies connected to the dark and bright spots on the Moon: in addition to the rabbit, there is also the idea of a toad or a crab. Instead of a man, a princess is seen there. There are various legends about...") Tags: Visual edit Disambiguation links |

Boshunyang (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE: Yuè (月, Moon)}} |

|||

Yuè (月) is a name for the Moon of the Earth in China. |

|||

{{distinguish|Yue (Constellation)}} |

|||

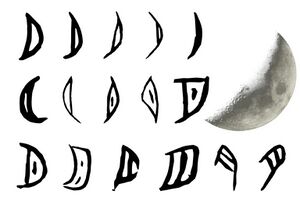

Yuè (月) in Chinese holds dual meanings: it refers tothe Moon of the Earth and a unit of time, equivalent to a month. The character "月" in oracle bone script 3000 years ago resembles a crescent moon, reflecting ancient Chinese observations of lunar phases. Symbolically, the Moon embodies poetic imagination, philosophical contemplation, and mythological narratives in Chinese culture, while its role in calendrical systems underscores its practical importance in agriculture and timekeeping. |

|||

[[File:The character Yue(月) in oracle bones 3000 years ago.jpg|thumb|The character Yue(月) in oracle bones more than 3000 years ago]] |

|||

==Name Variants and History== |

==Name Variants and History== |

||

What does the term mean, does it always have the same meaning - was it changed over time. |

|||

===Name Variants=== |

===Name Variants=== |

||

Ancient Chinese people had many variants for the moon name, most of which were elegant appellations coined in literary works based on certain attributes of the moon. Some names were metaphorical, derived from its shape or qualities—for instance, yù lún(玉轮, "jade wheel")or yù pán(玉盘, "jade disc"), likening the moon’s roundness and luminous clarity to fine jade or ornamental objects. Others stemmed from mythology, such as Cháng’é(嫦娥, "Chang’e"), yù tù(玉兔, "jade rabbit"), yù chán(玉蟾, "jade toad"), or Wàngshū(望舒, "Wangshu", the charioteer of the moon). Still others combined elements of both metaphor and myth. These names were not standardized, reflecting the creativity of the people. Besides, Tàiyīn(太阴, "Great Yin")was a relatively common epithet, rooted in the cosmological theory of yīn yáng(阴阳, "yin and yang"), and serving as the counterpart to the sun, or Tàiyáng(太阳, "Great Yang"). |

|||

===Dark Spots on the Moon=== |

===Dark Spots on the Moon=== |

||

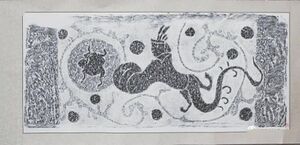

Since at least the Western Han period (202BCE to 8 CE), images depicting the moon have included the figures of a '''Jade Rabbit''' and/or a toad. Although we have no direct evidence, some suggests that these lunar creatures were inspired by the dark spots visible on the moon’s surface. Others have interpreted these markings as representing a cassia tree and the figure of '''Wu Gang''' from another myth. In modern times, some even imagine the spots as resembling a crab, though the origin of this association remains unknown. |

|||

In China, there is a huge variety of mythologies connected to the dark and bright spots on the Moon: in addition to the rabbit, there is also the idea of a toad or a crab. Instead of a man, a princess is seen there. |

|||

<gallery> |

|||

There are various legends about the woman in the moon and the man in the moon in East Asia: according to one legend, '''Chang'e''' consumed an elixir of immortality that her husband had won for his archery skills; according to another, she is a moon princess or moon goddess who visited Earth briefly but is actually immortal and belongs on the moon. She lives with the '''Jade Rabbit''' in a palace on the moon. '''Wu Gang''', the woodcutter, was condemned to cut down a certain olive tree on the moon, which, to his chagrin, has self-healing powers and always grows back. |

|||

File:Moon on the Mural Paintings of Western Han Tombs at Xi'an Jiaotong University.jpeg|Moon on the Mural Paintings of Western Han Tombs at Xi'an Jiaotong University |

|||

File:Moon on Nanyue Han Dynasty Azure Dragon Constellation Portrait Stone.jpg|Moon on Nanyang Han Dynasty Azure Dragon Constellation Portrait Stone |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

File:Imaginative illustrations of lunar surface dark spots and the figures of Jade Rabbit and Toad.jpg|Imaginative illustrations of lunar surface dark spots and the figures of Jade Rabbit and Toad |

|||

File:JadeHase smh2024.jpeg|The Jade Rabbit (玉兔 Yùtù) who makes the elixir of Life on the Moon (China). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

File: |

File:MondKroete HK2024.jpeg|The Moon Toad, 金蟾 (Jin Chan). |

||

File: |

File:ChangE HK2024.jpeg|Change'e (嫦娥 ''Cháng'é''), the immortal lady who flew to the Moon (China). |

||

| ⚫ | |||

File:MoonCrab HK2024.jpeg|The Moon Crab (China) |

File:MoonCrab HK2024.jpeg|The Moon Crab (China) |

||

File:ChangE HK2024.jpeg|Change'e, the immortal lady who flew to the Moon (China). |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

</gallery> |

</gallery> |

||

===Phases of the Moon<ref>Chen Meidong. Zhongguo gudai tianwenxue sixiang (Ancient Chinese Astronomical Thoughts). Beijing: Science and Technology Press of China. 2008, p. 227.</ref>=== |

|||

===Phases of the Moon=== |

|||

A rational understanding of the moon’s phases had already emerged by the Han dynasty. In the late first century BCE, the scholar Jīng Fáng(京房, "Jing Fang", 77 BCE - 37 BCE) recorded two prevailing theories of the time: one posited that both the sun and the moon were spherical, while the other held that the sun was spherical but the moon had a mirror-like surface. Zhāng Héng(张衡, "Zhang Heng", 78 - 139 CE) clearly adopted the former view and offered a coherent explanation for the changing lunar phases. He argued that the moon’s light originates from the sun light, and that its dark portion—referred to as the "po" (魄)—is caused by the obstruction of sunlight. Thus, a full moon occurs when the sun and moon are positioned opposite each other on the celestial sphere, whereas the illuminated portion gradually disappears as the moon approaches the sun.<ref>Qutan Xida. Kaiyuan Zhan Jing. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. 2012, p. 2.</ref> |

|||

Is there a scientific or mythological interpretation for the phases of the moon? |

|||

===Lunar Eclipse=== |

===Lunar Eclipse=== |

||

In ancient China, various explanations were offered for the causes of lunar eclipses. Some attributed them to mythical events, such as the moon being devoured by a toador to cosmic battles between sacred creatures like the ''qílín''(麒麟, "kirin")and ''lóng''(龙, "dragon"). These interpretations may be early precursors to the now widespread folk expression "the heavenly dog devours the moon". |

|||

explanation/ mythology/ rituals |

|||

During the Warring States and Qin-Han periods, after the formalization of ''yīn yáng''(阴阳, "yin and yang")theory, cosmologists of the ''Yīnyáng jiā''(阴阳家, "School of Yin and Yang")linked the sun with ''yáng''(阳, "yang")and the emperor, and the moon with ''yīn''(阴, "yin")and the empress or ministers . According to this framework, an eclipse signified an imbalance between yin and yang forces. A lunar eclipse, in particular, was interpreted as evidence that the yin force had become too weak.<ref>Chen Meidong. Zhongguo gudai tianwenxue sixiang (Ancient Chinese Astronomical Thoughts). Beijing: Science and Technology Press of China. 2008, p. 266-268.</ref> |

|||

At the same time, more scientific approaches to eclipses also emerged. Scholars like Zhang Heng proposed theories involving concepts such as ''ànxū''(暗虚, "shadowy void")and ''ànqì''(暗气, "obscuring vapor"). Among these, the ''ànxū'' theory gained wide acceptance. As described in the ''Língxiàn''(《灵宪》, "Spiritual Constitution"):<blockquote>“Moonlight is produced by the illumination of the sun… the stars shine because light is reflected through water. At the direct opposition to the sun, the light can't get together due to obstruction by the Earth. This is called the ‘shadowy void’ (''ànxū''). When it meets the star, then the stars will become faint; when the moon passes through it, an eclipse occurs.”(“月光生于日之所照……众星被耀,因水转光。当日之冲,光常不合者,蔽于地也。是谓暗虚,在星星微,月过则食。”)</blockquote>This passage describes a theory akin to the modern notion of Earth's shadow causing lunar eclipses: moonlight is reflected sunlight, and when the Earth obstructs that light—a shadow is cast, creating a so-called ''ànxū''.<ref>For a better understanding of the "Anxu" and lunar eclipse, see Li Zhichao. Zhang Heng de yueshi lilun (Zhang Heng's Theory of Lunar Eclipses). In "Tian ren gu yi (Ancient Meanings of Heaven and Man)". Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe. 1995, pp. 279-284.</ref> |

|||

However, alternative versions of the ''ànxū'' theory existed. For example, ''Xiāo Zǐxiǎn''(萧子显, "Xiao Zixian")of the Liang dynasty proposed:<blockquote>“The sun contains a mass of dark vapor (ànqì), and Heaven has a void path (xūdào). This path is always directly opposite the sun. When the moon moves within this void path, it is covered by the vapor, and thus a lunar eclipse occurs.”(“日有暗气,天有虚道,常与日冲相对,月行在虚道中,则为气所弇,故月为食也。”)<ref>Xiao Zixian. Nanqi shu (The Book of Southern Qi). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. 1972, p. 207.</ref></blockquote>In this view, the sun emits a mass of ''ànqì''(暗气, "dark vapor")that projects to a point directly opposite it, forming a dim zone in sunlight called ''ànxū''(暗虚). This zone follows a trajectory termed ''xūdào''(虚道, "void path"), thought to correspond to the ''huángdào''(黄道, "ecliptic"). When the moon passed through this zone, it was believed to be eclipsed as it was obscured by this vapor. |

|||

==Mythology== |

==Mythology== |

||

There are many myths about the moon in China, the most famous of which are Chang'e, the Toad and the Jade Rabbit, as well as Wu Gang and the Cassia Tree. |

|||

mnemonic tales and cultural significance |

|||

'''1.Chang'e, the Toad and the Jade Rabbit''' |

|||

The earliest Chinese geographical text, the ''Shānhǎi jīng · Dàhuāng xījīng''(《山海经·大荒西经》, ''Classic of Mountains and Seas: Western Wilderness'')contains a mythical account in which ''Chángxī''(常羲, "Changxi")is described bathing the twelve moons she had borne:<blockquote> ''“There was a woman bathing the moons. Changxi, the wife of Dì Jùn(帝俊, "Emperor Jun"), gave birth to twelve moons; this was the beginning of their bathing.”'' (“有女子方浴月。帝俊妻常羲,生月十有二,此始浴之。”)</blockquote>Some people believe that ''Chángxī'' later evolved into the more widely known figure of ''Cháng’é''(嫦娥, "Chang’e"). However, while Changxi in the ''Shānhǎi jīng'' is portrayed as the mother of the moons, Chang’e eventually became merely a solitary woman dwelling on the moon. This transformation may reflect shifts in cosmological understanding. As astronomical theory became more systematized in the last several centuries BCE, people came to realize that the sun and moon were immense celestial bodies—early estimates put their diameters at around 1,000 ''lǐ''(里, roughly 400 kilometers)—making the idea of a terrestrial moon-bathing ritual seem implausible. |

|||

The earliest textual reference to ''Cháng’é'' appears in the Warring States (475 - 221 BCE) text ''Guīcáng''(《归藏》, ''The Returning Storehouse''):<blockquote>“Long ago, Chang’e consumed the elixir of immortality belonging to the ''Xīwángmǔ''(西王母, a goddest in the west)and fled to the moon, becoming its spirit.”(“昔嫦娥以西王母不死之药服之,遂奔月为月精。”)</blockquote>A more developed version appears in the early Western Han text ''Huáinánzǐ · Lǎnmíng xùn''(《淮南子·览冥训》, ''Huainanzi: Surveying the Obscure''):<blockquote>“''Yì''(羿, the archer)requested the elixir of immortality from the ''Xīwángmǔ''. His wife ''Héng’é''(姮娥, another form of Chang’e)secretly fled to the moon, settle down there, became a toad, and thus became the spirit of the moon (''yuè jīng'' 月精).”(“羿请不死之药于西王母,羿妻姮娥窃奔月,托身于月,是为蟾蜍,而为月精。”) |

|||

In this version, ''Yì''(羿, "Yi"), the hero who shot down nine of the ten suns and saved humanity from drought, acquires the elixir. Chang’e consumes it without permission and ascends to the moon, transforming into a toad—an animal later closely associated with the lunar spirit. Han dynasty tomb reliefs frequently depict this imagery, reinforcing the link between Chang’e and the toad.[[File:The depiction of Chang'e and the toad in Han Dynasty stone carvings.jpeg|thumb|The depiction of Chang'e and the toad in Han Dynasty stone carvings]]</blockquote>The rabbit also appears in early moon mythology. During the late Warring States period, the Chu poet ''Qū Yuán''(屈原, "Qu Yuan", 342 - 287 BCE)mentioned a creature called ''gùtù''(顾菟, “leaping rabbit”)on the moon in his poem ''Tiānwèn''(《天问》, ''Heavenly Questions''). It is uncertain, however, whether this rabbit was originally related to Chang’e. It is possible that these myths developed independently and were later merged—eventually, the ''Yùtù''(玉兔, "Jade Rabbit")came to be regarded as Chang’e’s companion. |

|||

'''2. Wu Gang''' |

|||

The earliest known reference to the story of "Wu Gang Chopping the Cassia Tree" appears in the Tang dynasty (618 - 907) miscellany ''Yǒuyáng zázǔ · Tiān zhǐ''(《酉阳杂俎·天咫》, ''Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang: Proximities of Heaven'')by ''Duàn Chéngshì''(段成式):<blockquote>“It was traditionally said that in the moon there are a cassia tree (''guì'' 桂) and a toad. Thus, certain strange-books claim that the cassia tree reaches a height of five hundred ''zhàng''(丈, about 1,480 meters). Beneath it stands a man who constantly chops at the tree. Yet the wounds on the tree heal as soon as they are made. The man is named ''Wú Gāng''(吴刚, Wu Gang), a native of ''Xīhé''(西河, present-day Fenyang County, Shanxi Province). While studying the Daoist arts of immortality, he committed a transgression and was sentenced to chop the tree as punishment.” (“旧言月中有桂,有蟾蜍,故异书言,月桂高五百丈,下有一人,常斫之。树创随合。人姓吴名刚,西河人。学仙有过,谪令伐树。”)</blockquote>In this narrative, the cassia tree is portrayed as a sacred, self-healing tree that can never be felled, and Wu Gang is condemned to a Sisyphean task as retribution for some fault committed during his pursuit of Daoist immortality. The specific nature of his transgression, however, is not recorded in any known classical text. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

==Weblinks== |

==Weblinks== |

||

* |

* |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

*[[References]] (general) |

*[[References]] (general) |

||

[[Category:Moon]] [[Category:Asterism]] |

|||

[[Category:Moon Features]][[Category:Chinese]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 02:42, 7 June 2025

Yuè (月) in Chinese holds dual meanings: it refers tothe Moon of the Earth and a unit of time, equivalent to a month. The character "月" in oracle bone script 3000 years ago resembles a crescent moon, reflecting ancient Chinese observations of lunar phases. Symbolically, the Moon embodies poetic imagination, philosophical contemplation, and mythological narratives in Chinese culture, while its role in calendrical systems underscores its practical importance in agriculture and timekeeping.

Name Variants and History

Name Variants

Ancient Chinese people had many variants for the moon name, most of which were elegant appellations coined in literary works based on certain attributes of the moon. Some names were metaphorical, derived from its shape or qualities—for instance, yù lún(玉轮, "jade wheel")or yù pán(玉盘, "jade disc"), likening the moon’s roundness and luminous clarity to fine jade or ornamental objects. Others stemmed from mythology, such as Cháng’é(嫦娥, "Chang’e"), yù tù(玉兔, "jade rabbit"), yù chán(玉蟾, "jade toad"), or Wàngshū(望舒, "Wangshu", the charioteer of the moon). Still others combined elements of both metaphor and myth. These names were not standardized, reflecting the creativity of the people. Besides, Tàiyīn(太阴, "Great Yin")was a relatively common epithet, rooted in the cosmological theory of yīn yáng(阴阳, "yin and yang"), and serving as the counterpart to the sun, or Tàiyáng(太阳, "Great Yang").

Dark Spots on the Moon

Since at least the Western Han period (202BCE to 8 CE), images depicting the moon have included the figures of a Jade Rabbit and/or a toad. Although we have no direct evidence, some suggests that these lunar creatures were inspired by the dark spots visible on the moon’s surface. Others have interpreted these markings as representing a cassia tree and the figure of Wu Gang from another myth. In modern times, some even imagine the spots as resembling a crab, though the origin of this association remains unknown.

Phases of the Moon[1]

A rational understanding of the moon’s phases had already emerged by the Han dynasty. In the late first century BCE, the scholar Jīng Fáng(京房, "Jing Fang", 77 BCE - 37 BCE) recorded two prevailing theories of the time: one posited that both the sun and the moon were spherical, while the other held that the sun was spherical but the moon had a mirror-like surface. Zhāng Héng(张衡, "Zhang Heng", 78 - 139 CE) clearly adopted the former view and offered a coherent explanation for the changing lunar phases. He argued that the moon’s light originates from the sun light, and that its dark portion—referred to as the "po" (魄)—is caused by the obstruction of sunlight. Thus, a full moon occurs when the sun and moon are positioned opposite each other on the celestial sphere, whereas the illuminated portion gradually disappears as the moon approaches the sun.[2]

Lunar Eclipse

In ancient China, various explanations were offered for the causes of lunar eclipses. Some attributed them to mythical events, such as the moon being devoured by a toador to cosmic battles between sacred creatures like the qílín(麒麟, "kirin")and lóng(龙, "dragon"). These interpretations may be early precursors to the now widespread folk expression "the heavenly dog devours the moon".

During the Warring States and Qin-Han periods, after the formalization of yīn yáng(阴阳, "yin and yang")theory, cosmologists of the Yīnyáng jiā(阴阳家, "School of Yin and Yang")linked the sun with yáng(阳, "yang")and the emperor, and the moon with yīn(阴, "yin")and the empress or ministers . According to this framework, an eclipse signified an imbalance between yin and yang forces. A lunar eclipse, in particular, was interpreted as evidence that the yin force had become too weak.[3]

At the same time, more scientific approaches to eclipses also emerged. Scholars like Zhang Heng proposed theories involving concepts such as ànxū(暗虚, "shadowy void")and ànqì(暗气, "obscuring vapor"). Among these, the ànxū theory gained wide acceptance. As described in the Língxiàn(《灵宪》, "Spiritual Constitution"):

“Moonlight is produced by the illumination of the sun… the stars shine because light is reflected through water. At the direct opposition to the sun, the light can't get together due to obstruction by the Earth. This is called the ‘shadowy void’ (ànxū). When it meets the star, then the stars will become faint; when the moon passes through it, an eclipse occurs.”(“月光生于日之所照……众星被耀,因水转光。当日之冲,光常不合者,蔽于地也。是谓暗虚,在星星微,月过则食。”)

This passage describes a theory akin to the modern notion of Earth's shadow causing lunar eclipses: moonlight is reflected sunlight, and when the Earth obstructs that light—a shadow is cast, creating a so-called ànxū.[4] However, alternative versions of the ànxū theory existed. For example, Xiāo Zǐxiǎn(萧子显, "Xiao Zixian")of the Liang dynasty proposed:

“The sun contains a mass of dark vapor (ànqì), and Heaven has a void path (xūdào). This path is always directly opposite the sun. When the moon moves within this void path, it is covered by the vapor, and thus a lunar eclipse occurs.”(“日有暗气,天有虚道,常与日冲相对,月行在虚道中,则为气所弇,故月为食也。”)[5]

In this view, the sun emits a mass of ànqì(暗气, "dark vapor")that projects to a point directly opposite it, forming a dim zone in sunlight called ànxū(暗虚). This zone follows a trajectory termed xūdào(虚道, "void path"), thought to correspond to the huángdào(黄道, "ecliptic"). When the moon passed through this zone, it was believed to be eclipsed as it was obscured by this vapor.

Mythology

There are many myths about the moon in China, the most famous of which are Chang'e, the Toad and the Jade Rabbit, as well as Wu Gang and the Cassia Tree.

1.Chang'e, the Toad and the Jade Rabbit

The earliest Chinese geographical text, the Shānhǎi jīng · Dàhuāng xījīng(《山海经·大荒西经》, Classic of Mountains and Seas: Western Wilderness)contains a mythical account in which Chángxī(常羲, "Changxi")is described bathing the twelve moons she had borne:

“There was a woman bathing the moons. Changxi, the wife of Dì Jùn(帝俊, "Emperor Jun"), gave birth to twelve moons; this was the beginning of their bathing.” (“有女子方浴月。帝俊妻常羲,生月十有二,此始浴之。”)

Some people believe that Chángxī later evolved into the more widely known figure of Cháng’é(嫦娥, "Chang’e"). However, while Changxi in the Shānhǎi jīng is portrayed as the mother of the moons, Chang’e eventually became merely a solitary woman dwelling on the moon. This transformation may reflect shifts in cosmological understanding. As astronomical theory became more systematized in the last several centuries BCE, people came to realize that the sun and moon were immense celestial bodies—early estimates put their diameters at around 1,000 lǐ(里, roughly 400 kilometers)—making the idea of a terrestrial moon-bathing ritual seem implausible. The earliest textual reference to Cháng’é appears in the Warring States (475 - 221 BCE) text Guīcáng(《归藏》, The Returning Storehouse):

“Long ago, Chang’e consumed the elixir of immortality belonging to the Xīwángmǔ(西王母, a goddest in the west)and fled to the moon, becoming its spirit.”(“昔嫦娥以西王母不死之药服之,遂奔月为月精。”)

A more developed version appears in the early Western Han text Huáinánzǐ · Lǎnmíng xùn(《淮南子·览冥训》, Huainanzi: Surveying the Obscure):

“Yì(羿, the archer)requested the elixir of immortality from the Xīwángmǔ. His wife Héng’é(姮娥, another form of Chang’e)secretly fled to the moon, settle down there, became a toad, and thus became the spirit of the moon (yuè jīng 月精).”(“羿请不死之药于西王母,羿妻姮娥窃奔月,托身于月,是为蟾蜍,而为月精。”) In this version, Yì(羿, "Yi"), the hero who shot down nine of the ten suns and saved humanity from drought, acquires the elixir. Chang’e consumes it without permission and ascends to the moon, transforming into a toad—an animal later closely associated with the lunar spirit. Han dynasty tomb reliefs frequently depict this imagery, reinforcing the link between Chang’e and the toad.

The rabbit also appears in early moon mythology. During the late Warring States period, the Chu poet Qū Yuán(屈原, "Qu Yuan", 342 - 287 BCE)mentioned a creature called gùtù(顾菟, “leaping rabbit”)on the moon in his poem Tiānwèn(《天问》, Heavenly Questions). It is uncertain, however, whether this rabbit was originally related to Chang’e. It is possible that these myths developed independently and were later merged—eventually, the Yùtù(玉兔, "Jade Rabbit")came to be regarded as Chang’e’s companion.

2. Wu Gang

The earliest known reference to the story of "Wu Gang Chopping the Cassia Tree" appears in the Tang dynasty (618 - 907) miscellany Yǒuyáng zázǔ · Tiān zhǐ(《酉阳杂俎·天咫》, Miscellaneous Morsels from Youyang: Proximities of Heaven)by Duàn Chéngshì(段成式):

“It was traditionally said that in the moon there are a cassia tree (guì 桂) and a toad. Thus, certain strange-books claim that the cassia tree reaches a height of five hundred zhàng(丈, about 1,480 meters). Beneath it stands a man who constantly chops at the tree. Yet the wounds on the tree heal as soon as they are made. The man is named Wú Gāng(吴刚, Wu Gang), a native of Xīhé(西河, present-day Fenyang County, Shanxi Province). While studying the Daoist arts of immortality, he committed a transgression and was sentenced to chop the tree as punishment.” (“旧言月中有桂,有蟾蜍,故异书言,月桂高五百丈,下有一人,常斫之。树创随合。人姓吴名刚,西河人。学仙有过,谪令伐树。”)

In this narrative, the cassia tree is portrayed as a sacred, self-healing tree that can never be felled, and Wu Gang is condemned to a Sisyphean task as retribution for some fault committed during his pursuit of Daoist immortality. The specific nature of his transgression, however, is not recorded in any known classical text.

In any case, the person on the moon is linked to eternity, and that must be quite lonely in the long run, because eternity is quite long – especially towards the end.

In Buddhism, the moon is a symbol of truth and virtue, as these actually last relatively long (eternally).

Weblinks

References

- References (general)

- ↑ Chen Meidong. Zhongguo gudai tianwenxue sixiang (Ancient Chinese Astronomical Thoughts). Beijing: Science and Technology Press of China. 2008, p. 227.

- ↑ Qutan Xida. Kaiyuan Zhan Jing. Beijing: Jiuzhou Press. 2012, p. 2.

- ↑ Chen Meidong. Zhongguo gudai tianwenxue sixiang (Ancient Chinese Astronomical Thoughts). Beijing: Science and Technology Press of China. 2008, p. 266-268.

- ↑ For a better understanding of the "Anxu" and lunar eclipse, see Li Zhichao. Zhang Heng de yueshi lilun (Zhang Heng's Theory of Lunar Eclipses). In "Tian ren gu yi (Ancient Meanings of Heaven and Man)". Zhengzhou: Henan jiaoyu chubanshe. 1995, pp. 279-284.

- ↑ Xiao Zixian. Nanqi shu (The Book of Southern Qi). Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company. 1972, p. 207.