Crater: Difference between revisions

(created the page and added first content) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

* John McHugh (2016), How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms, Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies, 4(2), 69-100 |

* John McHugh (2016), How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms, Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies, 4(2), 69-100 |

||

* Kechagias and Hoffmann (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as a possible Source of Ancient Constellations, in Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.), Astronomy in Culture - Cultures of Astronomy, tredition, Ahrensburg, 205-234 |

* Kechagias and Hoffmann (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as a possible Source of Ancient Constellations, in Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.), Astronomy in Culture - Cultures of Astronomy, tredition, Ahrensburg, 205-234 |

||

[[Category:Constellation]] |

|||

[[Category:Greek]] |

|||

Revision as of 08:56, 6 March 2024

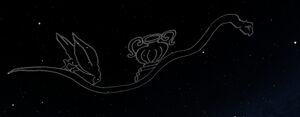

The constellation crater was created in antiquity, probably due to a wordplay. It is unknown whether it happened intentionally or unintentionally. The constellation forms part of the ancient Greek super-constellation of Hydra-Corvus-Crater. As such it is mentioned by Aratus, Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Ptolemy (and all Greek authors from Hellenistic time on). Greek mythology connects it to the adjacent constellations Hydra and Corvus, more details on mythology in Ian Ridpath's Star Tales.

Etymology & History

The pun which created the constellation

McHugh (2016) uses the term MUŠ stating that this Sumerian word has the Akkadian counterpart ``ṣēru'' (also meaning the snake). However, the Akkadian word ``ṣēru'' is a homonym, i. e. it has two meanings: it can denote a snake or a ceramic jug for wine. This way, astronomers from other cultures (e.g. the Mediterranean ones) could have confused the ṣēru (snake) with the ṣēru (crater) and thus put a crater on the back of Hydra. Compellingly, there is also a preposition ṣēru which means ``on top of, upon''. McHugh (2016, 87-88) therefore produces the phrase ``wine-bowl on top of the water-snake'' from the term MUŠ.

Kechagias and Hoffmann (2022) agree upon the first idea that the homophony but reject the latter part: "the intercultural misunderstandings of a Sumerian word to transform a special deity to a usual Water-Snake and of an homophonous Akkadian term to change a snake into a wine-bowl, are rather convincing. In contrast, deriving the presence of a raven at the snake's tail from cuneiform wordplays is considered by us as unnecessary."

Depiction of Crater in Antiquity

The snake-like constellation that called Hydra in Greek uranology used to be considered a straight line of stars at the celestial equator in the Sumerian and early Babylonian culture. It is depicted as a straight snake-body until Seleucid period, in particular on the microzodiac clay tablets VAT 7847 and AO 6448. This traditional view is also represented on the preserved Greek silver globe (Galérie Kugel, Paris). However, on the marble Farnese Globe which is dated to Hellenistic time, the Hydra snake has a dip towards south which forms a vessel for the smaller sub-constellations of Crater and Corvus. This way of depiction is reproduced in Roman and mediaeval images, possibly originally depicting the pun that the "snake" simultanously "is" the jar that it contains.

References

- John McHugh (2016), How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms, Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies, 4(2), 69-100

- Kechagias and Hoffmann (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as a possible Source of Ancient Constellations, in Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.), Astronomy in Culture - Cultures of Astronomy, tredition, Ahrensburg, 205-234