Wangliang: Difference between revisions

Boshunyang (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

Boshunyang (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{DISPLAYTITLE: Wangliang (王良)}} |

{{DISPLAYTITLE: Wangliang (王良)}} |

||

Wáng Liáng (王良) is a Chinese constellation comprises five stars located within the Cassiopeia. It was created by the Shi school in Western Han dynasty, based on the incorporation and integration of earlier constellations. |

|||

== Concordance, Etymology, History == |

== Concordance, Etymology, History == |

||

=== Origin of the Name === |

=== Origin of the Name === |

||

“Driving” (yu御) was one of the Liuyi(six arts六藝) prescribed in the Zhou li |

“Driving” (yu御) was one of the Liuyi(six arts六藝) prescribed in the ''Zhou li'' (Rites of Zhou周禮), serving as a compulsory subject in the education of noblemen. Wang Liang was the charioteer of Zhao Jianzi (趙簡子, ? - 476BCE), a grandee of the Jin state in the late Spring and Autumn period (770 - 476 BCE), celebrated for his exceptional skill in handling horses; thus, many classical texts praised his mastery. Some sources identify him as the legendary horse appraiser Bole (伯樂). |

||

The earliest extant historical reference to Wang Liang appears in the section ''Duke Ai, 2nd year'' (493 BCE) of ''Zuo zhuan'' (The Commentary of Zuo, compiled in 4 th century BCE):“You Wuxu(郵無恤) served as charioteer for Jianzi.” The authoritive commentator Du Yu (杜預) notes, “You Wuxu was Wang Liang.” At this stage, Wang Liang still appeared as an ordinary historical figure. In ''Mengzi'' (Mencius孟子, compiled around 300 BCE), the story of Zhao Jianzi and Wang Liang portrays the latter as a noble-minded charioteer who refused to share a carriage with a petty man. By the late Warring States period, Han Fei (韓非, 281 BCE - 233BCE), in his political philosophy, depicted Wang Liang as a sagacious man who comprehended the Way of governance through his perfect mastery of charioteering. In early Han texts such as Huainanzi (淮南子, completed in 139 BCE), imbued with Daoist ideas, his art of driving horses is elevated to the level of a sage’s practice in accord with the principle of wuwei (non-action): |

The earliest extant historical reference to Wang Liang appears in the section ''Duke Ai, 2nd year'' (493 BCE) of ''Zuo zhuan'' (The Commentary of Zuo, compiled in 4 th century BCE):“You Wuxu(郵無恤) served as charioteer for Jianzi.” The authoritive commentator Du Yu (杜預) notes, “You Wuxu was Wang Liang.” At this stage, Wang Liang still appeared as an ordinary historical figure. In ''Mengzi'' (Mencius孟子, compiled around 300 BCE), the story of Zhao Jianzi and Wang Liang portrays the latter as a noble-minded charioteer who refused to share a carriage with a petty man. By the late Warring States period, Han Fei (韓非, 281 BCE - 233BCE), in his political philosophy, depicted Wang Liang as a sagacious man who comprehended the Way of governance through his perfect mastery of charioteering. In early Han texts such as Huainanzi (淮南子, completed in 139 BCE), imbued with Daoist ideas, his art of driving horses is elevated to the level of a sage’s practice in accord with the principle of wuwei (non-action):<blockquote>“In ancient times,the good chariotters like Wang Liang and Zaofu, upon ascending the carriage and taking the reins, the horses aligned in harmony, moving with even rhythm; their exertion and rest were one, the heart and breath in accord, the body light and balanced; they advanced with joy and effortlessness, galloping as if vanishing.”</blockquote>Although these accounts belong to different literary traditions—historical, philosophical, and Daoist—they clearly illustrate the gradual sanctification of Wang Liang’s image. It is therefore plausible that his ascent into the heavens as a stellar figure occurred between the late Warring States and early Han periods, when his persona had been fully transformed into that of a sage. |

||

“In ancient times,the good chariotters like Wang Liang and Zaofu, upon ascending the carriage and taking the reins, the horses aligned in harmony, moving with even rhythm; their exertion and rest were one, the heart and breath in accord, the body light and balanced; they advanced with joy and effortlessness, galloping as if vanishing.” |

|||

Although these accounts belong to different literary traditions—historical, philosophical, and Daoist—they clearly illustrate the gradual sanctification of Wang Liang’s image. It is therefore plausible that his ascent into the heavens as a stellar figure occurred between the late Warring States and early Han periods, when his persona had been fully transformed into that of a sage. |

|||

=== Identification of stars === |

=== Identification of stars === |

||

| ⚫ | The earliest record of Wang Liang as a star name appears in ''Shiji''史記, “Tiangaunshu” (Book of Heaven Officials, 天官書):<blockquote>“Within the (Celestial) River are four stars called Tian Si (Heavenly Quadriga, 天駟). Beside them is one star named Wang Liang. When Wang Liang drives the horses, the (war) chariots will fill the fields.”</blockquote>At this stage, Wang Liang referred to a single star positioned next to the four stars of Tian Si, forming the image of a charioteer driving four horses abreast. Perhaps because these two asterisms constituted a coherent cultural unit, the ''Shishi xing jing'' (Shi’s Star Canon, 石氏星經) later combined them under the unified name Wang Liang. Some scholars have suggested that the ''Shi’s Star Canon'' originated as early as the fourth century BCE, yet the case of Wang Liang makes such an early date less probable, since the process of deification and celestial integration appears to have occurred later, in the Warring States–Han transition. |

||

The earliest record of Wang Liang as a star name appears in ''Shiji''史記, “Tiangaunshu” (Book of Heaven Officials, 天官書): |

|||

“Within the (Celestial) River are four stars called Tian Si (Heavenly Quadriga, 天駟). Beside them is one star named Wang Liang. When Wang Liang drives the horses, the (war) chariots will fill the fields.” |

|||

| ⚫ | At this stage, Wang Liang referred to a single star positioned next to the four stars of Tian Si, forming the image of a charioteer driving four horses abreast. Perhaps because these two asterisms constituted a coherent cultural unit, the ''Shishi xing jing'' (Shi’s Star Canon, 石氏星經) later combined them under the unified name Wang Liang. Some scholars have suggested that the ''Shi’s Star Canon'' originated as early as the fourth century BCE, yet the case of Wang Liang makes such an early date less probable, since the process of deification and celestial integration appears to have occurred later, in the Warring States–Han transition. |

||

{| class="wikitable" |

{| class="wikitable" |

||

|+ |

|+ |

||

| Line 27: | Line 19: | ||

Based on catalogue in 18th century |

Based on catalogue in 18th century |

||

!Pan Nai<ref name=":0">Pan Nai潘鼐. ''Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi''中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 1989. p226.</ref> |

!Pan Nai<ref name=":0">Pan Nai潘鼐. ''Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi''中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 1989. p226.</ref> |

||

based on Xinyixiangfayao Star Map |

based on Xinyixiangfayao Star Map and Huangyou Catalogue |

||

!Pan Nai<ref>Pan Nai潘鼐. ''Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi''中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 2009. p443.</ref> |

|||

based on catalogues in Yuan dynasty |

|||

!SUN X. & J. Kistemaker<ref>Sun Xiaochun. & Kistemaker J. ''The Chinese sky during the Han''. Leiden: Brill. 1997, Pp241-6.</ref> |

!SUN X. & J. Kistemaker<ref>Sun Xiaochun. & Kistemaker J. ''The Chinese sky during the Han''. Leiden: Brill. 1997, Pp241-6.</ref> |

||

Han Dynasty |

Han Dynasty |

||

| Line 38: | Line 28: | ||

|- |

|- |

||

| 1st/Determinative/Wangliang |

| 1st/Determinative/Wangliang |

||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| beta Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 2nd/Tiansi |

| 2nd/Tiansi |

||

| kappa Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| kappa Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| gamma Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| gamma Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| gamma Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| gamma Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

| 3rd/Tiansi |

| 3rd/Tiansi |

||

| gamma Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|4th/Tiansi |

|4th/Tiansi |

||

| |

| eta Cas |

||

| alpha Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| alpha Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| alpha Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| alpha Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| alpha Cas |

|||

| x |

|||

| x |

|||

|- |

|- |

||

|5th/Tiansi |

|5th/Tiansi |

||

|alpha Cas |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

|lambda Cas |

|||

| |

|||

|zeta Cas |

|||

| |

|||

|zeta Cas |

|||

| |

|||

|zeta Cas |

|||

| |

|||

|zeta Cas |

|||

| |

|||

| |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

In astrological interpretation, the constellation Wang Liang bore two principal meanings. The first regarded it as the emperor’s charioteer—by extension, symbolizing royal carriages and military escorts. The second viewed it as King’s bridges and official in charge of crossings over celestial water, likely because it lies within the Milky Way. Corresponding to these two aspects, Wang Liang was also known by various alternate names: those such as Tian Qi (Heavenly Cavalry, 天騎) and Tian Ma (Heavenly Horse, 天馬) reflect the first sense, while Tianjin (Heavenly Bridge/Ferry, 天津), Wang Liang (King’s Bridge, 王梁), Tianqiao (Heavenly Bridge, 天橋), and Xiqiao (Western Bridge, 西橋) reflect the second. These meanings suggests the existence of previously distinct astrological traditions. For instance, the ''Tianguan shu'' records only the first interpretation. However, the ''Shi’s Star Canon'' integrates both, implying a deliberate effort to harmonize diverse earlier schools. |

In astrological interpretation, the constellation Wang Liang bore two principal meanings. The first regarded it as the emperor’s charioteer—by extension, symbolizing royal carriages and military escorts. The second viewed it as King’s bridges and official in charge of crossings over celestial water, likely because it lies within the Milky Way. Corresponding to these two aspects, Wang Liang was also known by various alternate names: those such as Tian Qi (Heavenly Cavalry, 天騎) and Tian Ma (Heavenly Horse, 天馬) reflect the first sense, while Tianjin (Heavenly Bridge/Ferry, 天津), Wang Liang (King’s Bridge, 王梁), Tianqiao (Heavenly Bridge, 天橋), and Xiqiao (Western Bridge, 西橋) reflect the second. These meanings suggests the existence of previously distinct astrological traditions. For instance, the ''Tianguan shu'' records only the first interpretation. However, the ''Shi’s Star Canon'' integrates both, implying a deliberate effort to harmonize diverse earlier schools. |

||

| Line 97: | Line 82: | ||

!same in Stellarium 24.4 |

!same in Stellarium 24.4 |

||

|- |

|- |

||

|[[File: |

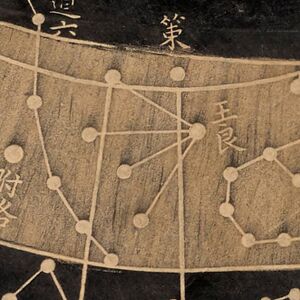

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce in Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunyajido.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce in ''Cheonsang Yeolcha Bunyajido'']] |

||

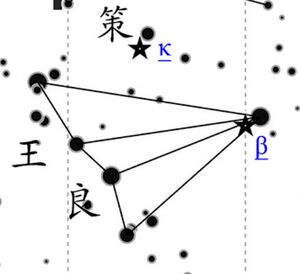

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce Reconstructed by Boshun Yang (2023) based on Huangyou Star Catalogue in 1052 CE.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce Reconstructed by Boshun Yang (2023) based on Huangyou Star Catalogue in 1052 CE]] |

|||

| |

|||

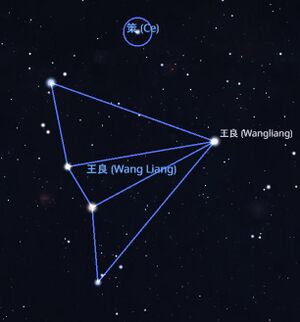

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce before 17th Century in Stellarium.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce before 17th Century in Stellarium]] |

|||

| |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

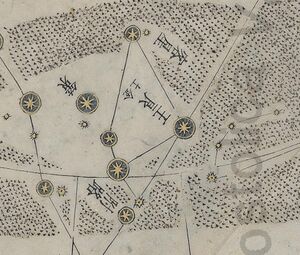

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce in Jesuits Star Map in 17th Century.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce in Jesuits Star Map in 17th Century]] |

|||

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce Reconstructed by Yi Shitong (1981) based on Qing Star Catalogue in 18th Century.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce Reconstructed by Yi Shitong (1981) based on Qing Star Catalogue in 18th Century]] |

|||

|[[File:Wangliang and Ce after 17th Century in Stellarium.jpg|thumb|Wangliang and Ce after 17th Century in Stellarium]] |

|||

|} |

|} |

||

Latest revision as of 20:42, 31 October 2025

Wáng Liáng (王良) is a Chinese constellation comprises five stars located within the Cassiopeia. It was created by the Shi school in Western Han dynasty, based on the incorporation and integration of earlier constellations.

Concordance, Etymology, History

Origin of the Name

“Driving” (yu御) was one of the Liuyi(six arts六藝) prescribed in the Zhou li (Rites of Zhou周禮), serving as a compulsory subject in the education of noblemen. Wang Liang was the charioteer of Zhao Jianzi (趙簡子, ? - 476BCE), a grandee of the Jin state in the late Spring and Autumn period (770 - 476 BCE), celebrated for his exceptional skill in handling horses; thus, many classical texts praised his mastery. Some sources identify him as the legendary horse appraiser Bole (伯樂).

The earliest extant historical reference to Wang Liang appears in the section Duke Ai, 2nd year (493 BCE) of Zuo zhuan (The Commentary of Zuo, compiled in 4 th century BCE):“You Wuxu(郵無恤) served as charioteer for Jianzi.” The authoritive commentator Du Yu (杜預) notes, “You Wuxu was Wang Liang.” At this stage, Wang Liang still appeared as an ordinary historical figure. In Mengzi (Mencius孟子, compiled around 300 BCE), the story of Zhao Jianzi and Wang Liang portrays the latter as a noble-minded charioteer who refused to share a carriage with a petty man. By the late Warring States period, Han Fei (韓非, 281 BCE - 233BCE), in his political philosophy, depicted Wang Liang as a sagacious man who comprehended the Way of governance through his perfect mastery of charioteering. In early Han texts such as Huainanzi (淮南子, completed in 139 BCE), imbued with Daoist ideas, his art of driving horses is elevated to the level of a sage’s practice in accord with the principle of wuwei (non-action):

“In ancient times,the good chariotters like Wang Liang and Zaofu, upon ascending the carriage and taking the reins, the horses aligned in harmony, moving with even rhythm; their exertion and rest were one, the heart and breath in accord, the body light and balanced; they advanced with joy and effortlessness, galloping as if vanishing.”

Although these accounts belong to different literary traditions—historical, philosophical, and Daoist—they clearly illustrate the gradual sanctification of Wang Liang’s image. It is therefore plausible that his ascent into the heavens as a stellar figure occurred between the late Warring States and early Han periods, when his persona had been fully transformed into that of a sage.

Identification of stars

The earliest record of Wang Liang as a star name appears in Shiji史記, “Tiangaunshu” (Book of Heaven Officials, 天官書):

“Within the (Celestial) River are four stars called Tian Si (Heavenly Quadriga, 天駟). Beside them is one star named Wang Liang. When Wang Liang drives the horses, the (war) chariots will fill the fields.”

At this stage, Wang Liang referred to a single star positioned next to the four stars of Tian Si, forming the image of a charioteer driving four horses abreast. Perhaps because these two asterisms constituted a coherent cultural unit, the Shishi xing jing (Shi’s Star Canon, 石氏星經) later combined them under the unified name Wang Liang. Some scholars have suggested that the Shi’s Star Canon originated as early as the fourth century BCE, yet the case of Wang Liang makes such an early date less probable, since the process of deification and celestial integration appears to have occurred later, in the Warring States–Han transition.

| Star Names or Orders(Qing) | Ho PENG YOKE[1] | Yi Shitong[2]

Based on catalogue in 18th century |

Pan Nai[3]

based on Xinyixiangfayao Star Map and Huangyou Catalogue |

SUN X. & J. Kistemaker[4]

Han Dynasty |

Boshun Yang[5]

before Tang dynasty |

Boshun Yang[5]

Song Jingyou(1034) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st/Determinative/Wangliang | beta Cas | beta Cas | beta Cas | beta Cas | beta Cas | beta Cas |

| 2nd/Tiansi | kappa Cas | kappa Cas | gamma Cas | gamma Cas | gamma Cas | gamma Cas |

| 3rd/Tiansi | gamma Cas | eta Cas | eta Cas | eta Cas | eta Cas | eta Cas |

| 4th/Tiansi | eta Cas | alpha Cas | alpha Cas | alpha Cas | alpha Cas | alpha Cas |

| 5th/Tiansi | alpha Cas | lambda Cas | zeta Cas | zeta Cas | zeta Cas | zeta Cas |

Astrological Significance

In astrological interpretation, the constellation Wang Liang bore two principal meanings. The first regarded it as the emperor’s charioteer—by extension, symbolizing royal carriages and military escorts. The second viewed it as King’s bridges and official in charge of crossings over celestial water, likely because it lies within the Milky Way. Corresponding to these two aspects, Wang Liang was also known by various alternate names: those such as Tian Qi (Heavenly Cavalry, 天騎) and Tian Ma (Heavenly Horse, 天馬) reflect the first sense, while Tianjin (Heavenly Bridge/Ferry, 天津), Wang Liang (King’s Bridge, 王梁), Tianqiao (Heavenly Bridge, 天橋), and Xiqiao (Western Bridge, 西橋) reflect the second. These meanings suggests the existence of previously distinct astrological traditions. For instance, the Tianguan shu records only the first interpretation. However, the Shi’s Star Canon integrates both, implying a deliberate effort to harmonize diverse earlier schools.

Additionally, a nearby star known as Ce (Whip, 策) was believed to represent the charioteer’s whip. This star was most likely added during the Western Han period.

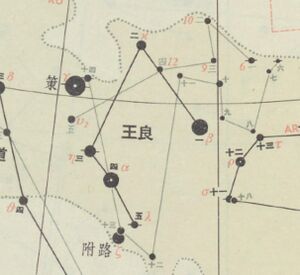

Maps (Gallery)

As a bright and easily recognizable constellation, Wang Liang maintained consistent identification throughout the traditional period. Only in the seventeenth century, with the introduction of European astronomy, did Jesuit astronomers and Chinese scholars collaborating on the revision of the celestial charts alter the membership of the constellation.

| historical map | modern identification

(Yang 2023) |

same in Stellarium 24.4 |

|---|---|---|

Star Name Discussion (IAU)

In 202x, the name of the historical constellation "xxx" was suggested to be used for one of the stars in this constellation. ...

Decision: ...

References

- ↑ P.-Y. Ho, “Ancient And Mediaeval Observations of Comets and Novae in Chinese Sources,” Vistas in Astronomy, 5(1962), 127-225.

- ↑ Yi Shitong伊世同. Zhongxi Duizhao Hengxing Tubiao中西对照恒星图表1950. Beijing: Science Press.1981: 56.

- ↑ Pan Nai潘鼐. Zhongguo Hengxing Guance shi中国恒星观测史[M]. Shanghai: Xuelin Pree. 1989. p226.

- ↑ Sun Xiaochun. & Kistemaker J. The Chinese sky during the Han. Leiden: Brill. 1997, Pp241-6.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 B.-S. Yang杨伯顺, Zhongguo Chuantong Hengxing Guance Jingdu ji Xingguan Yanbian Yanjiu 中国传统恒星观测精度及星官演变研究 (A Research on the Accuracy of Chinese Traditional Star Observation and the Evolution of Constellations), PhD thesis, (Hefei: University of Science and Technology of China, 2023). 261.