Taurus

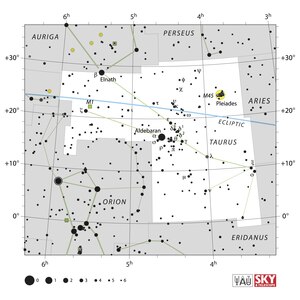

One of the 88 IAU constellations. For the star cluster-asterisms of the Pleiades and the Hyades see separate entry.

Etymology and History

The shape of a bull is quite easily recognisable in the sky in this asterism. Two open star clusters stand out prominently: the Hyades and the Pleiades. They are sometimes seen as the pillars of a gate through which the sun, moon and planets pass. By adding further stars, they become the figure of half a bull. Greek mythology explains the absence of the back of the bull by the fact that it is swimming.

In reality, of course, the zodiacal constellation - like all the others - is taken from Mesopotamia.

Origin of Constellation

Originally, the celestial bull is part of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. Gilgamesh was king of Sumer, the southern part of Mesopotamia, in the 3rd millennium. It is unclear how long this king actually lived and ruled, but he is documented in a list of kings. Perhaps several kings (of the same name) are mixed up there. The figure of Gilgamesh in literature symbolises a number of cultural upheavals or as a founder of culture.

The most important city in Sumer was Uruk, whose city goddess is Inanna/Ishtar. After Gilgamesh and his friend Enkidu had already performed other heroic deeds, they fight together in Uruk against the celestial bull sent by Ishtar: the bull belonged to Ishtar's father, the sky god Anu, and was therefore a deity or mythical creature. The heroes succeed in defeating the beast when Enkidu grabs the bull from behind and Gilgamesh grabs it from the front. This explains the bisected constellation.

Some researchers see the Mesopotamian constellations Hired Man (today: Aries) and True Shepherd of the Heavens (today: Orion) as a representation of this bullfight between Enkidu (Hired Man on the invisible hindquarters of the bull) and Gilgamesh. The figure of Orion stretches out one hand towards the bull's head and, according to the Almagest, swings a club with the other as if to hit the bull between the horns - as reported in the Epic of Gilgamesh (tablet 6). In addition, the shepherd figure (for humans) is a metaphor for rulers, which can be traced back to Sumerian times for kings and lives on today in the symbolism of Christian bishops. However, the divine shepherd is typically Dumuzi, Ishtar's husband, assigned to the labourer's constellation. The connection between the constellations Ori-Tau-Ari is therefore very speculative without written evidence. Writing as a cultural technique had only just been invented at this time. Only a few commercial documents and no astronomical texts have survived from the 3rd millennium.

Greco-Roman

Aratos

Near the feet o f the Charioteer look for the horned Bull crouching. This constellation is very recognisable, so clearly defined is its head: one needs no other sign to identify the ox’s head, so well do the stars themselves model both sides of it as they go round. Their name is also very popular: the Hyades are not just nameless. They are set out all along the Bull’s face; the point of its left horn and the right foot o f the adjacent Charioteer are occupied by a single star, and they are pinned together as they go. But the Bull is always ahead o f the Charioteer in sinking to the horizon, though it rises simultaneously. (Kidd 1997)

Eratosthenes[5]

From Pamias and Zucker (2013) translated to English by us.

Variant 1 (p. 45-46)

It is said that he was placed among the constellations for having carried Europa across the sea from Phoenicia to Crete, as Euripides recounts in his Phrixos. This earned him Zeus's distinction and a place among the most visible constellations. Others claim that it is a cow, the replica of Io, and that it was out of consideration for the latter that it [the constellation] received this privilege from Zeus.

The stars named Hyades define the contours of the forehead and face of Taurus. At the break in the image of Taurus, at the height of the back, is the Pleiades, which has seven stars, and that is why it is also given the name ‘Heptaster’ (seven stars). In reality, only six are visible, as the seventh is completely unremarkable.

Taurus has seven stars, and it moves backwards with its head tucked towards its body: one at the base of each of its horns —the brightest being the one on the left—, one above each eye, one above each nostril, one above each shoulder: these are called ‘the Hyades’; it also has one on its left front knee, two on its hooves, one on its right knee, two on its neck, three on its back —the last of which is bright—, one under its belly, and one bright star on its chest. In all, eighteen.

Variant 2 (p.47)

It is said that he was placed among the constellations for having carried Europa safely across the sea from Phoenicia to Crete, as Euripides recounts in his Phrixos. This earned him Zeus's distinction and a place among the most visible constellations. Others claim that it is a cow that is among the constellations, the replica of Io; out of consideration for the latter, she received this privilege from Zeus.

The stars named ‘Hyades’ define the contours of the bull's forehead and face; Phercydes of Athens says that they are the nurses of Dionysus, known as the ‘nymphs of Dodona’. Taurus has a star on each of its horns, two on its forehead, one on each eye, one on each nostril (the latter are called ‘the Hyades’); it also has one on its front knee, two on its neck, three on its back, one on its hoof, one on its right knee, two on its belly, and one on its chest. Eighteen in all.

Hipparchus

Hyginus, Astronomica

The Bull was placed among the stars because it carried Europa safely to Crete, as Euripides says. Some say that when Io was transformed into a heifer, Jupiter, to seem to make amends, put an image among the constellations which resembled a bull in its fore parts, but was dim behind. It faces towards the East, and the stars which outline the face are called Hyades. These, Pherecydes the Athenian says, are the nurses of Liber, seven in number, who earlier were nymphae called Dodonidae. Their names are as follows: Ambrosia, Eudora, Pedile, Coronis, Polyxo, Phyto, and Thyone. They are said to have been put to flight by Lycurgus and all except Ambrosia took refuge with Thetis, as Asclepiades says. But according to Pherecydes, they brought Liber to Thebes and delivered him to Ino, and for this reason Jove expressed his thanks to them by putting them among the constellations.

The Pleiades were so named, according to Musaeaus, because fifteen daughters were born to Atlas and Aethra, daughter of Ocean. Five of them are called Hyades, he shows, because their brother was Hyas, a youth dearly beloved by his sisters. When he was killed in a lion hunt, the five we have mentioned, given over to continual lamentation, are said to have perished. Because they grieved exceedingly at his death, they are called Hyades. The remaining ten brooded over the death of their sisters, and brought death on themselves; because so may experienced the same grief, they were called Pleiades. Alexander says they were called Hyades because they were daughters of Hyas and Boeotia, Pleiades, because born of Pleio, daughter of Ocean, and Atlas.

The Pleiades are called seven in number, but only six can be seen. This reason has been advanced, that of the seven, six mated with immortals (three with Jove, two with Neptune, and one with Mars); the seventh was said to have been the wife of Sisyphus. From Electra and Jove, Dardanus was born; from Maia and Jove, Mercury; from Taygete and Jove, Lacedaemon; from Alcyone and Neptune, Hyrieus; from Celaeno and Neptune, Lycus and Nycteus. Mars by Sterope begat Oinomaus, but others call her the wife of Oinomaus. Merope, wed to Sisyphus, bore Glaucus, who, as many say, was the father of Bellerophon. On account of her other sisters she was placed among the constellations, but because she married a mortal, her star is dim. Others say Electra does not appear because the Pleiades are thought to lead the circling dance for the stars, but after Troy was captured and her descendants through Dardanus overthrown, moved by grief she left them and took her place in the circle called Arctic. From this she appears, in grief for such a long time, with her hair unbound, that, because of this, she is called a comet.

But ancient astronomers placed these Pleiades, daughters of Pleione and Atlas, as we have said, apart from the Bull. When Pleione once was travelling through Boeotia with her daughters, Orion, who was accompanying her, tried to attack her. She escaped, but Orion sought her for seven years and couldn't find her. Jove, pitying the girls, appointed a way to the stars, and later, by some astronomers, they were called the Bull's tail. And so up to this time Orion seems to be following them as they flee towards the west. Our writers call these stars Vergiliae, because they rise after spring. They have still greater honour than the others, too, because their rising is a sign of summer, their setting of winter — a thing is not true of the other constellations. (Mary Ward 1960)

Almagest Ταῦρος

| id | Greek

(Heiberg 1898) |

English

(Toomer 1984) |

ident. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ταύρου ἀστερισμός | Constellation of Taurus | ||

| 1 | τῶν ἐν τῇ ἀποτομῇ δ’ ὁ βόρειος. | The northernmost of the 4 stars in the cut-off | 5 Tau |

| 2 | ὁ ἐχόμενος αὐτοῦ. | The one close by this | 4 Tau |

| 3 | ὁ ἔτι τούτου ἐχόμενος. | The one close again to the latter | xi Tau |

| 4 | ὁ νοτιώτατος τῶν δ | The southernmost of the 4 | omi Tau |

| 5 | ὁ τούτοις ἐπόμενος ἐπὶ τῆς δεξιᾶς ὡμοπλάτης | The one to the rear of these, on the right shoulder-blade | 30 Tau |

| 6 | ὁ ἐε τῷ στήθει | The star in the ehest | lam Tau |

| 7 | ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ δεξιοῦ γόρατος | The star on the right knee | mu Tau |

| 8 | ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ δεξιοῦ σφυροῦ | The star on the right hock | nu Tau |

| 9 | ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ ἀριστεροῦ γόνατος | The star an the left knee | 90 Tau |

| 10 | ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ ἀριστεροῦ πήχεως | The star on the left lower leg | 88 Tau |

| 11 | τῶν ἐν τῷ προσώπῳ καλουμένων Τάδων ὁ ἐπὶ τῶν μυκτήρων | The stars in the face, called 'the Hyades': the one on the nostrils | gam Tau |

| 12 | ὁ μεταξὺ τούτου καὶ τοῦ βορεύου ὀφθαλμοῦ | The stars in the face, called 'the Hyades': the one between this and the northern eye | del1 Tau |

| 13 | ὁ μεταξὺ αὐτοῦ καὶ τοῦ φοτύου ὀφδαλμοῦ | The stars in the face, called 'the Hyades': the one between it [ no. 11] and the southern eye | tet1 Tau |

| 14 | ὁ λαμπρὸς τῶν Ῥάδων ἐπὶ τοῦ νοτίου ὀφθαλμοῦ ὑπόκιρρος | The stars in the face, called 'the Hyades': the bright star ofthe Hyades, the reddishone on the southern eye | alf Tau |

| 15 | ὁ λοιπὸς καὶ ἐπὶ τοῦ βορεύου ὀφθαλμοῦ | The stars in the face, called 'the Hyades': the remaining one, on the nordlern eye | eps Tau |

| 16 | ὁ ἐπὶ τῆς ἐκφύσεως τοῦ νοτίου κέρατος καὶ τοῦ ὠτίου | The star on the place where the southern horn and the ear join [the head] | 97 Tau |

| 17 | ὁ τῶν ἐπὶ τοῦ φοτίου κέρατος β ὁ νοτιώτερος | The southernmost of the 2 stars on the southern horn | 104 Tau |

| 18 | ὁ βορειότερος αὐτῶν | The northernmost of these | 106 Tau |

| 19 | ὁ ἐπ’ ἄκρου τοῦ νοτίου κέρατος | The star on the tip of the southern horn | zet Tau |

| 20 | ὁ ἐπὶ τῆς ἐκφύσεως τοῦ βορείου κέρατος. | The star on the place where the northern horn joins [ the head] | tau Tau |

| 21 | ὁ ἐπ’ ἄκρου τοῦ βορείου κέρατος ὁ αὐτὸς τῷ ἐπὶ τοῦ δεξιοῦ ποδὸς τοῦ Ἡνιόχου. | The star on the tip of the northern horn, which is the same as the one on right foot of Auriga | bet Tau |

| 22 | τῶν ἐν τῷ βορείῳ ὠτίῳ β σύνεγγυς ὁ βορειότερος | The northernmost of the 2 stars close tagether in the northern ear | ups Tau |

| 23 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐτῶν. | The southernmost of them | kap Tau |

| 24 | τῶν ἐν τῷ τραχήλῳ β μικρῶν ὁ προηγούμενος | The more advanced of the 2 small stars in the neck | 37 Tau |

| 25 | ὁ ἐπόμενος αὐτῶν | The rearmost of them | omega Tau |

| 26 | τοῦ ἐν τῷ αὐχένι τετραπλεύρου τῆς προηγουμένης πλευρᾶς ὁ νοτιώτερος | The quadrilateral in the neck: the southernmost star on the advance side | 44 Tau |

| 27 | ὁ βορειότερος τῆς προηγουμένης πλευρᾶς | The quadrilateral in the neck: the northernmost star on the advance side | psi Tau |

| 28 | τῆς ἐπομένης πλευρᾶς ὁ νοτιώτερος | The quadrilateral in the neck: the southernmost star on the rear side | chi Tau |

| 29 | ὁ βορειότερος τῆς ἐπομένης πλευρᾶς. | The quadrilateral in the neck: the northernmost one on the rear side | phi Tau |

| 30 | τῆς Πλειάδος τὸ βόρειου πέρας τῆς ἠγουμένης πλευρᾶς | The Pleiades: the northern end of the advance side | 19 Tau |

| 31 | τὸ νότιον πέρας τῆς ἠγουμένης πλευρᾶς | The Pleiades: the southern end of the advance side | 23 Tau |

| 32 | τὸ ἐπόμενου καὶ στεηότατον πέρας τῆς Πλειάδος. | The Pleiades: the rearmost and narrowest end of the Pleiades | 27 Tau |

| 33 | ὁ ἔκτος καὶ μικρὸς τῆς Πλειάδος ἀπ’ ἄρκτων | The Pleiades: the small star outside the Pleiades, towards the north | HR 1188 |

| ἀστέρες λβ, ὥν αἱ μεγέθουςα, γ’ς, δ’ ἴἄ, ε φ, ς’ α. | 32 stars, 1 of the first magnitude, 6 of the third, 11 of the fourth, 13 of the ftfth, 1 of the sixth | ||

| Οἱ περὶ τὸν Ταῦρον ἀμόρφωτου. | Stars araund Taurus outside the constellation: | ||

| 34 | ὁ ὑπὸ τὸν δεξιὸν πόδα καὶ τὴν ὡμοπλάτην. | The star under the right foot and the shoulder-blade | 10 Tau |

| 35 | τῶν ὑπὲρ τὸ νότιον κέρας γ’ ὁ προηγούμενος. | The most advanced of the 3 stars over the southern horn | iot Tau |

| 36 | ὁ μέσος τῶν τριῶν. | The middle one of the three | 109 Tau |

| 37 | ὁ ἐπόμενος αὐτῶν. | The rearmost of them | 114 Tau |

| 38 | τῶν ὑπὸ τὸ ἄκρου τοῦ νοτίου κέρατος β’ ὁ βορειότερος. | The northernmost of the 2 stars under the tip of the southern horn | 126 Tau |

| 39 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐτῶν. | The southernmost of them | 129 Tau |

| 40 | τῶν ὑπὸ τὸ βόρειον κέρας ἓ ἐπομένων ὁ προηγούμενος. | The 5 Stars under and to the rear of the northern horn: the most advanced | 121 Tau |

| 41 | ὁ τούτῳ ἑπόμενος. | The 5 Stars under and to the rear of the northern horn: the one to the rcar of thi's | 125 Tau |

| 42 | ὁ ἔτι τούτῳ ἐπόμενος. | The 5 Stars under and to the rear of the northern horn: the one to the rear again of the latter | 132 Tau |

| 43 | τῶν λοιπῶν καὶ ἐπομένωυ β ὁ βορειότερος. | The 5 Stars under and to the rear of the northern horn: the northernmost of the remaining, rearmost 2 | 136 Tau |

| 44 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐτῶν. | The 5 Stars under and to the rear of the northern horn: the southernmost of these two | 139 Tau |

| ἀστέρες ιὰ, ὧν δ’ μεγέθους ἄ, 8 ἱ. | {ll stars, I of the fourth magnitude, I 0 of the fifth} |

Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation

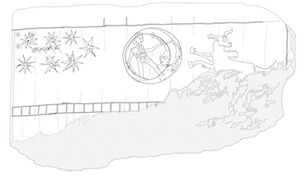

Taurus sign on clay tablet VAT 7851 with drawings of Pleiades (Bristle), Hyades (Chariot), Bull, and the Moon during a total lunar eclipse in the Moon's hypsoma; drawing by Hoffmann (2025)[6]

Greek Mythology

The most famous of the Greek myths about the bull is the abduction of Princess Europa of Phoenicia. Zeus had transformed himself into a bull, she played with him, sat on his back and then he galloped into the water and swam to Crete. Euripides tells this story and also found its way into astronomical literature via Eratosthenes. Today, the motif is depicted on Greek 2 euro coins.

Mythographers favour the Pleiades story of the nymph Pleione and her seven daughters, who supposedly want to remain virgins but are pursued by the lustful Orion. They apparently do not achieve their goal of eternal virginity, because each of them becomes pregnant: none by Orion. Six of them give birth to sons of the gods, one of them - Merope - marries the mortal Sisyphus (from the Greek ‘merops’, mortal).

In Mesopotamia, the Celestial Bull is undoubtedly from the Epic of Gilgamesh:

Gilgamesh was a cruel ruler under whom his subjects suffered. The gods therefore created a companion for him. This one, Enkidu, had grown up among animals and represents the moral antithesis to Gilgamesh: He criticises the ruler's cruelty. After a wrestling match, they become friends and set off together to cut down trees in the sacred cedar forest. First they have to defeat the guardian of this forest, which they succeed in doing, but afterwards Enkidu regrets the deed because the forest is no longer so beautiful and is inhabited and ‘animated’ by animals. Next they come to Uruk, where the city goddess offers Gilgamesh to become her husband. He refuses, pointing out that her other suitors have fared badly. Ishtar then complains to her father Anu and asks him for the Bull of Heaven to set him on Gilgamesh, who has insulted her. Anu points out that the city of Uruk and its inhabitants are threatened with great famine if he is brought down to earth, but Ishtar says that she has made provisions for the people. Nevertheless, 300 men fall victim to this bull before Enkidu and Gilgamesh slaughter it and sacrifice it to the sun god.

Enkidu must atone for this deed with death and Gilgamesh, who initially sets out in search of the herb of life for immortality, finally realises that there are more important things than power and violence and that immortality can only be achieved through good deeds. He invents the city wall to pacify Uruk and becomes a good king.

A bull associated with the sun is a fairly common religious motif: it also appears in the contemporary Egyptian deity Apis and later in the cult of Mithras.

Weblinks

- Ridpath, Ian, “Star Tales: online edition”.

References

- ↑ Hoffmann, S.M. (2025). Image Analysis of VAT 7851, Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO) 56, 45-53

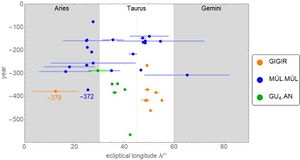

- ↑ Hoffmann, S. M. and Hunger, H. (2024). Terminology in Taurus, The Bull. Nouvelles Assyriologiques Brèves et Utilitaires, 4, 121

- ↑ Hoffmann, S.M. (2025). Image Analysis of VAT 7851, Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO) 56, 45-53

- ↑ Hoffmann (2025), Some Results on the Ancient Globes, Globe Studies – The Journal of the International Coronelli Society, 69, 4169.

- ↑ Ératosthènes de Cyrène: Catastérrismes, translated by Pamìas, Jordi und Zucker, Arnaud, Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2013

- ↑ Hoffmann, S.M. (2025). Image Analysis of VAT 7851, Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO) 56, 45-53