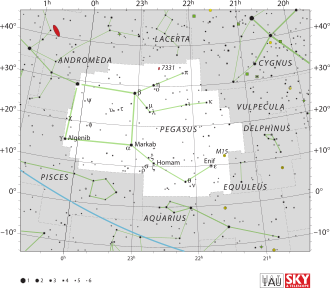

Pegasus

One of the 88 IAU constellations. The ancient Greek constellation has always been called The Horse (without wings). However, the mythology associated with it has simultaneously always left Pegasus, the winged horse, as one of several options.

Etymology and History

The poet Hesiod (8th century BCE) presents a folk etymology of the name Pegasus as derived from πηγή pēgē 'spring, well', referring to "the pegai of Okeanos, where he was born".

Origin of Constellation

Ancient Greco-Roman Ίππος Horse

In Greek,[1] this constellation is simply called a Horse, and the authors argue about which horse it is and what it does in the sky. Aratos states that the hoofbeat of this horse created the Hippocrene, the source of the horse below the eastern peak of Mount Helicon, north of Corinth. He implies that it could be Pegasus, but Eratosthenes also quotes nameless ‘other’ authors who do not believe this because the horse has no wings in the sky.

Euripides, on the other hand, identifies the horse with Hippe, the daughter of the wise centaur Cheiron, who wanted to hide her pregnancy from her father. Even after being transformed into a horse, she hides her abdomen, which is why only the horse's upper body is visible. Moreover, she is never in the sky at the same time as the centaur because she is hiding from him.

Aratos' Wording

...

Eratosthenes' Wording

You can only see half of it, with only the front part visible, up to the navel. According to Aratos this is the horse of Helicon, who, with a blow from his hoof the spring that is now called the ‘Spring of the Horse’ (Hippocrene). However, according to others, it was Pegasus, the horse that flew up to the stars after the fall of Bellerophon; nevertheless, some people find this interpretation not very credible, given that the figure does not wings. As for Euripides, in his Melanippe, that among the stars it is Hippe, the daughter of Chiron. It is said that she was brought up on the Pelion, practised hunting, and devoted herself to the observation and study of nature. Aeolus abused her and raped her, but she was for a time to conceal the fact; but when it when it became obvious, because of the roundness of her belly, she fled to the mountains. She was about to give birth when her father went into the mountains to look for her. untains; when she was discovered, she prayed she prayed to the gods to be metamorphosed and transformed into a horse so that she would not be recognised. So she was transformed into a horse and gave birth to a foal. Also, because of her piety and that of her father, she was placed by Artemis among the constellations, and this is why it was impossible for the Centaur to see her; it is said, in fact, that the Centaur is none other than Chiron. Hippe's posterior parts are invisible, precisely so that no one so that we do not know that she is female.

The horse has two stars on its nostrils, one on its head one on the head, one on the jaw, one on each of the ears four on the neck, one also on the shoulder, one on the chest one on the chest, one on the back, one bright, at the edge of the on the navel, two on the front knees, and one on each hoof. Eighteen in all.

(Pamias and Zucker 2013)[2]

Three Ancient Globes

Terminology

For mathematical astronomy, the constellation was always called ‘The Horse’; this is beyond question for Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Ptolemy. For Eratosthenes, it is wingless, Ptolemy records a star below the wing; for Hipparchus, this cannot be decided because his star catalogue has not survived. The didactic poem by Aratos was part of basic education in antiquity (for everybody, not only scholars), i.e. it was much better known than the scholarly texts on mathematical astronomy. The memorable hexameters could be useful as farming rules, and even if the weather in Central Europe differed from that in the Mediterranean region, some statements about the seasons could also be utilised there. The interpretation of the winged horse survives both in the Arabic Middle Ages with aṣ-Ṣūfī and in Latin with the Carolingians, not only because of the popularity of the poem, but also because there were still ancient illustrations at the time that no longer exist today. Manuscripts such as the Leiden Aratea from the Carolingian period and the impressive illustrations in aṣ-Ṣūfī in Iran bear witness to this.

Ptolemy's Almagest

| Greek

(Heiberg 1898) |

English

(Toomer 1984) |

ident. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ὁ έπὶ τοῦ ὀμφαλοῦ κοινὸς τῆς κεφαλῆς τῆς ᾿Αvδρομέδας | The star on the navel, which is [applied in] common to the head of Andromeda | α And |

| 2 | ὁ έπὶ τῆς ὀσφύος καὶ ἄκροv τού πτεροῦ. | The star on the rump and the wing-tip | γ Peg |

| 3 | ὁ ἐπὶ τού δεξιού ὤμου καὶ τῆς του ποδος ἐκφύσεως | The star on the right shou!der and the p!ace where the leg joins [it] | β Peg |

| 4 | ὁ ἐπί τού μεταφρένου καὶ τού ὤμοv τῆς πτέρvγος | The star on the place between the shoulders and the shoulder-part of the wing | α Peg |

| 5 | τῶν ἐν τῷ σώματι ὑπὸ τὴν πτέρυγα δύο ὁ βορειότερος | The northernmost of the two stars in the body under the wing | τ Peg |

| 6 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐτῶν | The southernmost of them | υ Peg |

| 7 | τῶν ἐν τῷ δεξιῷ γόνατι δύο ὁ βορειότερος | The northernmost of the two stars in the right knee | η Peg |

| 8 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐτῶν | The southernmost of them | ο Peg |

| 9 | των έν τφ στήθει δύο σύνεγγυς ὁ προηγούμενος | The more advanced of the two stars close together in the chest | λ Peg |

| 10 | ὁ ἐπόμενος αὐτῶν | The rearmost of them | μ Peg |

| 11 | τῶν ἐν τῷ τραχήλῳ β σύνεγγυς ὁ προηγούμενος | The more advanced of the 2 stars close together in the neck | ζ Peg |

| 12 | ὁ ἐπόμενος αὐτῶν | The rearmost of them | ξ Peg |

| 13 | τῶν ἐπὶ τῆς χαίτης δύο ὁ νοτιώτερος | The southernmost of the two stars on the mane | ρ Peg |

| 14 | ὁ βορειότερος αὐτῶv | The northernmost of them | σ Peg |

| 15 | τῶν ἐπὶ τῆς κεφαλῆς β σύνεγγυς ὁ βορειότερος | The northernmost of the two stars close tagether on the head | θ Peg |

| 16 | ὁ νοτιώτερος αὐ τῶν | The southernmost of them | ν Peg |

| 17 | ὁ ἐν τῷ ρύγχει | The star in the muzzle | ε Peg |

| 18 | ὁ ἐν τῷ δεξιῷ σφυρῷ | The star in the right hock | π Peg |

| 19 | ὁ ἐπι τοῦ ἀριστεροῦ γόνατος | The star· on the left knee | ι Peg |

| 20 | ὁ ἐν τῷ ἀριστερῷ σφvρῷ | The star in the left hock | κ Peg |

{20 stars, 4 of the second magnitude, 4 of the third, 9 of the fourth, 3 of the fifth}

Babylonian Predecessor

The Babylonian constellation[1] in this area of the sky was the quadrilateral (the one that is now called the 'autumn square' among amateur astronomers of Europe and North America). The Babylonian quadrilateral has the technical name mulIKU ("One Field"), an area measure for arable land similar to our hectare. It is also considered the seat of Ea, a god of wisdom and magic (he is depicted in the constellation Aquarius, Mesopotamian GU.LA, The Giant).

In this case, too, the Greek constellation, which dates back to archaic times, could go back to the Babylonian model: The Sumerian loanword ‘IKU’ sounds very similar (almost homophonous) to the word for horse in the Mycenaean dialect of Greek: ‘Iqo’.[4][5] Coupled with the ambiguity of the obsolete Mesopotamian vocabulary, this could easily have led to a (deliberate or inadvertent) reinterpretation.

Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation

Medieval Latin manuscript below:

The oldest scientific manuscript in the National Library the volume contains various Latin texts on astronomy. The volume, written in Caroline minuscule, consists of two sections, the first (ff. 1-26) copied c. 1000, in the Limoges area of France, probably in the milieu of Adémar de Chabannes (989-1034), whilst the second (ff. 27-50), from a scriptorium in the same region, may be dated c. 1150.

al-Sufi's representation below:

The constellation Pegasus ("The Winged or Flying Horse") as depicted in the influential star atlas of the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (10th cent.). In this beautifully illustrated copy, made around 1435 for the Samarkand astronomer-ruler Ulugh Beg, the constellation is shown as depicted on a celestial globe (i.e. mirrored as seen in the night sky).The brighter stars are labelled in Arabic which accurately translate the Greek names listed in the star catalogue of Claudius Ptolemy's Almagest (2nd cent.). The four brightest stars, forming the easily recognisable "Square of Pegasus" visible in the autumn and the winter night skies, are labelled Matn al-Faras ("The Horse's Back" = Alpha Pegasi), Mankib al-Faras ("The Horse's Shoulder" = Beta Pegasi), Surrat al-Faras ("The Horse's Navel" = Alpha Andromedae) and Jinah al-Faras ("The Horse's Wing" = Gamma Pegasi).The names for these stars in common use in recent centuries, which were recently adopted by the IAU WGSN,are Markab (Alpha Pegasi), Scheat (Beta Pegasi), Alpheratz (Alpha Andromedae), and Algenib (Gamma Pegasi).The modern constellation Pegasus also contains the star designated 51 Pegasi, which hosts the first exoplanet discovered (in 1995) around a solar-type star. As a result of the NameExoWorld contest organized by the IAU, the star is now named Helvetios (and the exoplanet, designated 51 Pegasi b, is named Dimidium).The compass directions are labelled in red, i.e. the top is west, bottom is east, left is south and right is north.Image details: BnF ms. Arabe 5036, fol. 93r.

Mythology

Weblinks

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hoffmann, Susanne M. Wie der Löwe an den Himmel kam. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2021

- ↑ Ératosthènes de Cyrène: Catastérrismes, translated by Pamìas, Jordi und Zucker, Arnaud, Les Belles Lettres, Paris 2013

- ↑ Hoffmann, S.M. (2021). Das babylonische Kompendium MUL.APIN: Messung von Zeit und Raum, in: Meller H., Reichenberger A. und Risch R. (Hrsg.), Zeit ist Macht: Wer macht Zeit? Time is power. Who makes Time? Tagungsband 13. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag, in: Tagungen des Landesmuseums für Vorgeschichte, Bd. 24, Halle 251-275

- ↑ McHugh, J. (2016), `How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms', Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 4/2, 69--100.

- ↑ Kechagias, A.-E. and Hoffmann, S.M. (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as possible source of ancient constellations. in: Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.). Astronomy in Culture – Cultures of Astronomy, tredition Hamburg/ OpenScienceTechnology Berlin, 205-235