Pegasus: Difference between revisions

(created a first entry text) |

(added leiden aratea and ancient globes) |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==== Ancient Greco-Roman ''Ίππος'' Horse ==== |

==== Ancient Greco-Roman ''Ίππος'' Horse ==== |

||

In Greek,<ref name=":0">Hoffmann, Susanne M. Wie der Löwe an den Himmel kam. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2021</ref> this constellation is simply called a Horse and the authors argue about which horse it is and what it does in the sky. '''Aratos''' states that the hoofbeat of this horse created the Hippocrene, the source of the horse below the eastern peak of Mount Helicon north of Corinth. He implies that it could be Pegasus, but '''Eratosthenes''' also quotes nameless ‘other’ authors who do not believe this because the horse has no wings in the sky. |

In Greek,<ref name=":0">Hoffmann, Susanne M. Wie der Löwe an den Himmel kam. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2021</ref> this constellation is simply called a Horse, and the authors argue about which horse it is and what it does in the sky. '''Aratos''' states that the hoofbeat of this horse created the Hippocrene, the source of the horse below the eastern peak of Mount Helicon, north of Corinth. He implies that it could be Pegasus, but '''Eratosthenes''' also quotes nameless ‘other’ authors who do not believe this because the horse has no wings in the sky. |

||

'''Euripides''', on the other hand, identifies the horse with Hippe, the daughter of the wise centaur Cheiron, who wanted to hide her pregnancy from her father. Even after being transformed into a horse, she hides her abdomen, which is why only the horse's upper body is visible. Moreover, she is never in the sky at the same time as the centaur because she is hiding from him. |

'''Euripides''', on the other hand, identifies the horse with Hippe, the daughter of the wise centaur Cheiron, who wanted to hide her pregnancy from her father. Even after being transformed into a horse, she hides her abdomen, which is why only the horse's upper body is visible. Moreover, she is never in the sky at the same time as the centaur because she is hiding from him. |

||

==== Three Ancient Globes ==== |

|||

| ⚫ | For '''mathematical astronomy''', the constellation was always called ‘'''The Horse'''’; this is beyond question for Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Ptolemy. For Eratosthenes, it is wingless, Ptolemy records a star below the wing |

||

<gallery> |

|||

File:Peg kugel.jpg|Horse (without wings) on the Kugel Globe; 1st century BCE |

|||

File:Peg mainz.jpg|Winged Horse on Mainz Globe (2nd century CE). |

|||

File:FarneseSMH2017 web 28.jpg|winged Horse on Farnese Globe (2nd century CE based on Hellenistic template) |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

[[File:Aratea fol. 32v.jpg|thumb|Pegasus in the Leiden Aratea (c. 830 CE).]] |

|||

| ⚫ | For '''mathematical astronomy''', the constellation was always called ‘'''The Horse'''’; this is beyond question for Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Ptolemy. For Eratosthenes, it is wingless, Ptolemy records a star below the wing; for Hipparchus, this cannot be decided because his star catalogue has not survived. The didactic poem by Aratos was part of basic education in antiquity (for everybody, not only scholars), i.e. it was much better known than the scholarly texts on mathematical astronomy. The memorable hexameters could be useful as farming rules, and even if the weather in Central Europe differed from that in the Mediterranean region, some statements about the seasons could also be utilised there. The interpretation of the winged horse survives both in the Arabic Middle Ages with aṣ-Ṣūfī and in Latin with the Carolingians, not only because of the popularity of the poem, but also because there were still ancient illustrations at the time that no longer exist today. Manuscripts such as the '''Leiden Aratea''' from the Carolingian period and the impressive illustrations in aṣ-Ṣūfī in Iran bear witness to this. |

||

==== Babylonian Predecessor ==== |

==== Babylonian Predecessor ==== |

||

The Babylonian constellation<ref name=":0" /> in this area of the sky was the quadrilateral (the one that is now called the 'autumn square' among amateur astronomers of Europe and North America). The Babylonian quadrilateral has the technical name [[IKU]] ("One Field"), an area measure for arable land similar to our hectare. It is also |

The Babylonian constellation<ref name=":0" /> in this area of the sky was the quadrilateral (the one that is now called the 'autumn square' among amateur astronomers of Europe and North America). The Babylonian quadrilateral has the technical name [[IKU]] ("One Field"), an area measure for arable land similar to our hectare. It is also considered the seat of Ea, a god of wisdom and magic (he is depicted in the constellation [[Aquarius]], Mesopotamian [[GU.LA]], The Giant). |

||

In this case, too, the Greek constellation, which dates back to archaic times, could go back to the Babylonian model: The Sumerian loanword ‘IKU’ sounds very similar (almost homophonous) to the word for horse in the Mycenaean dialect of Greek: ‘Iqo’.<ref>McHugh, J. (2016), `How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms', Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 4/2, 69--100.</ref><ref>Kechagias, A.-E. and Hoffmann, S.M. (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as possible source of ancient constellations. in: Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.). Astronomy in Culture – Cultures of Astronomy, tredition Hamburg/ OpenScienceTechnology Berlin, 205-235</ref> Coupled with the ambiguity of the obsolete Mesopotamian vocabulary, this could easily have led to a (deliberate or inadvertent) reinterpretation. |

In this case, too, the Greek constellation, which dates back to archaic times, could go back to the Babylonian model: The Sumerian loanword ‘IKU’ sounds very similar (almost homophonous) to the word for horse in the Mycenaean dialect of Greek: ‘Iqo’.<ref>McHugh, J. (2016), `How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms', Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 4/2, 69--100.</ref><ref>Kechagias, A.-E. and Hoffmann, S.M. (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as possible source of ancient constellations. in: Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.). Astronomy in Culture – Cultures of Astronomy, tredition Hamburg/ OpenScienceTechnology Berlin, 205-235</ref> Coupled with the ambiguity of the obsolete Mesopotamian vocabulary, this could easily have led to a (deliberate or inadvertent) reinterpretation. |

||

Revision as of 17:17, 17 April 2025

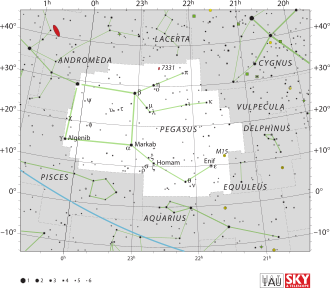

One of the 88 IAU constellations. The ancient Greek constellation has always been called The Horse (without wings). However, the mythology associated with it has simultaneously always left Pegasus, the winged horse, as one of several options.

Etymology and History

The poet Hesiod (8th century BCE) presents a folk etymology of the name Pegasus as derived from πηγή pēgē 'spring, well', referring to "the pegai of Okeanos, where he was born".

Origin of Constellation

Ancient Greco-Roman Ίππος Horse

In Greek,[1] this constellation is simply called a Horse, and the authors argue about which horse it is and what it does in the sky. Aratos states that the hoofbeat of this horse created the Hippocrene, the source of the horse below the eastern peak of Mount Helicon, north of Corinth. He implies that it could be Pegasus, but Eratosthenes also quotes nameless ‘other’ authors who do not believe this because the horse has no wings in the sky.

Euripides, on the other hand, identifies the horse with Hippe, the daughter of the wise centaur Cheiron, who wanted to hide her pregnancy from her father. Even after being transformed into a horse, she hides her abdomen, which is why only the horse's upper body is visible. Moreover, she is never in the sky at the same time as the centaur because she is hiding from him.

Three Ancient Globes

For mathematical astronomy, the constellation was always called ‘The Horse’; this is beyond question for Eratosthenes, Hipparchus and Ptolemy. For Eratosthenes, it is wingless, Ptolemy records a star below the wing; for Hipparchus, this cannot be decided because his star catalogue has not survived. The didactic poem by Aratos was part of basic education in antiquity (for everybody, not only scholars), i.e. it was much better known than the scholarly texts on mathematical astronomy. The memorable hexameters could be useful as farming rules, and even if the weather in Central Europe differed from that in the Mediterranean region, some statements about the seasons could also be utilised there. The interpretation of the winged horse survives both in the Arabic Middle Ages with aṣ-Ṣūfī and in Latin with the Carolingians, not only because of the popularity of the poem, but also because there were still ancient illustrations at the time that no longer exist today. Manuscripts such as the Leiden Aratea from the Carolingian period and the impressive illustrations in aṣ-Ṣūfī in Iran bear witness to this.

Babylonian Predecessor

The Babylonian constellation[1] in this area of the sky was the quadrilateral (the one that is now called the 'autumn square' among amateur astronomers of Europe and North America). The Babylonian quadrilateral has the technical name mulIKU ("One Field"), an area measure for arable land similar to our hectare. It is also considered the seat of Ea, a god of wisdom and magic (he is depicted in the constellation Aquarius, Mesopotamian GU.LA, The Giant).

In this case, too, the Greek constellation, which dates back to archaic times, could go back to the Babylonian model: The Sumerian loanword ‘IKU’ sounds very similar (almost homophonous) to the word for horse in the Mycenaean dialect of Greek: ‘Iqo’.[2][3] Coupled with the ambiguity of the obsolete Mesopotamian vocabulary, this could easily have led to a (deliberate or inadvertent) reinterpretation.

Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation

Mythology

Weblinks

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hoffmann, Susanne M. Wie der Löwe an den Himmel kam. Franckh Kosmos Verlag, Stuttgart 2021

- ↑ McHugh, J. (2016), `How Cuneiform Puns Inspired Some of the Bizarre Greek Constellations and Asterisms', Archaeoastronomy and Ancient Technologies 4/2, 69--100.

- ↑ Kechagias, A.-E. and Hoffmann, S.M. (2022). Intercultural Misunderstandings as possible source of ancient constellations. in: Hoffmann and Wolfschmidt (eds.). Astronomy in Culture – Cultures of Astronomy, tredition Hamburg/ OpenScienceTechnology Berlin, 205-235