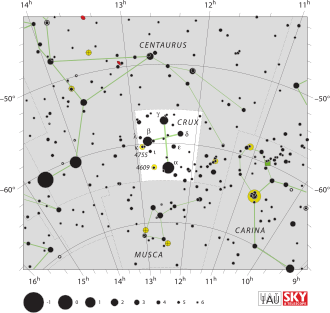

Crux

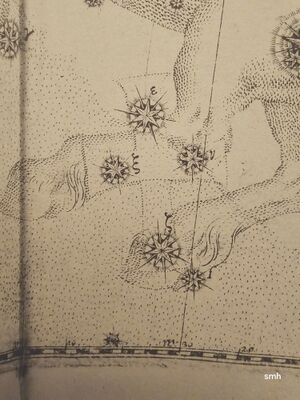

One of the 88 IAU constellations. In antiquity the four stars were part of the constellation Centaurus. Specifically, Bayer's Uranometria 1603 shows a superimposition of the images of Centaurus and a cross. Bayer certainly adopted this from Petrus Plancius and Joducus Hondius, but their globes and maps have not survived. The earliest mention (and drawing) of the cross is preserved in letters by Vespucci's navigator Corsali to their sponsors, the de Medici family from Florence. Therefore, many scholars connect the invention to the "quattro stelle" in Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy.[1] The practical reason for the invention might have been navigation (triangulation of the celestial south pole).

Etymology and History

The stars of this figure were already recorded in ancient star catalogues, but no Christian symbol could be placed in the sky before the invention of Christianity. In antiquity, the stars belonged to the centaur (Centaurus), forming its hind leg.

During the Portuguese voyages to India and the South Seas, the stars were used for navigation. The hind leg of the centaur was already pointing to the south celestial pole at the beginning of the 16th century and was therefore quite suitable for navigation. Andreas Corsali, an Italian who was travelling for the Medici merchant family and sailed from Lisbon to India in 1516, described the four stars as an incomparably beautiful celestial sign. No earlier mention of this figure is known.

For Corsali, asterism was initially a navigational aid, but Christian cartographers and astronomers adopted this figure as a constellation of its own on their globes and maps. The idea obviously caught the spirit of the times, as Petrus Plancius had also renamed the Greek ship Argo Noah's Ark around 1600. Even before he was aware of the navigational aid, he had suggested grouping other stars in the southern sky to form a cross. This is where the desire for Christianisation and the necessities of ocean navigation came together. The constellation of the cross was finally introduced at the latest with its adoption in Bayer's Uranometria in 1603, which still provides one of the standard nomenclatures today.

Origin of Constellation

Corsali

The navigator Corsali is regarded as a very well educated man who was proficient in both the Latin language and astronomy. He was in contact with the de Medici family and his letters[2] Lettera di Andrea Corsali allo Illustrissimo Signore Duca Iuliano de Medici, Venuta Dellindia del Mese di Octobre Nel M.D.XVI28F29 (Letters from Andrea Corsali to the Most Reverend Sir Iuliano di Medici, arrived from India in October 1516)[3] contain the first evidence of the constellation Crux. Significantly, both the de Medici family and Corsali came from Florence: Corsali was born in a smaller town only 20 kilometres southwest of the city.

The formulation that Ridpath quotes above is strongly reminiscent of the formulation of the Florentine Dante Alighieri[4][5] in his Comedia (Purg. I 23-24):[6]

- a l'altro polo, e vidi quattro stelle

- non viste mai fuor ch'a la prima gente.

Since it is obvious that the educated Corsali knew his compatriot's tercines, it is assumed that he wanted to memorialise Dante's abstract imagination in his navigational stars. Corsali was thus inspired by Dante and the constellation Crux is Christian in two senses: on the one hand, it represents the symbol of Christianity, the cross of Jesus, and on the other, what Dante himself meant by it. Whether he had a specific pattern of stars, a constellation or an asterism, in mind is doubtful: In his time European voyages of discovery were not yet very common (it was the time when the Jesuit Marco Polo lived in China and thus initiated the exchange of knowledge with East Asia) and mapping of the southern starry sky had not yet taken place. Dante scholars assume that Dante himself meant these four stars primarily as a physical performance of the Christian cardinal virtues - whether they also had a non-allegorical meaning for him is disputed. With the four virtues, Christianity stands in the tradition of Greek antiquity (they are already documented in Plato), which is entirely in Dante's sense when he repeatedly attempts to demonstrate the virtuousness of pre-Christian authors.

Dante

In his Divine Comedia,[6] Dante uses the starry sky as a kind of stage set.[7] He refers to it in several of his works like an eternal backdrop. In particular, the realm of his god, which he reaches at the end of his journey to the afterlife in the Comedia, is staged with the splendour of nature's jewellery on the velvet-black tent of the night. They are a perpetual guide on earth and, from Dante's point of view, disappear in hell. If black is the mourning colour of the Christian world, the darkness of the night has an oppressively gloomy effect. However, after a journey to hell, as Dante describes it, the stars appear as a ray of light, showing him that he has now reached a higher level (of realisation or even of consciousness in the encounter with Beatrice).

It is commonly assumed that his "quattro stelle" are symbols for the four cardinal virtues:

- prudence,

- justice,

- valour and

- temperance.

Like many things in Christianity, they can be traced back to much older Greek sources because they are basic human values. For example, they were also described by Aeschylus and Plato. Virgil accompanies Dante throughout his journey to the afterlife, even acting as Dante's guide. As Virgil (died 19 BCE) could not have been baptised a Christian, he is denied paradise according to Christian doctrine. This is one of the many aspects of Christianity that Dante criticizes in his Commedia: these virtues are - as he stresses - universal and not solely Christian.

Almagest

In Ptolemy's Almagest, the stars of Crux form the hind leg of Centaurus.

| id | Greek

(Heiberg 1898) |

English

(Toomer 1984) |

ident. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | ὁ ἐπὶ τῆς ἀγκύλης τοῦ δεξιοῦ ποδός | The star on the knee-bend of the right [bind] leg | γ Cru |

| 32 | ὁ ἐν τῷ σφυρῷ τοῦ αὐτοῦ ποδός | The star in the hock of the same leg | β Cru |

| 33 | ὁ ὑπὸ τὴν ἀγκύληη τοῦ ἀριστεροῦ ποδός | The star under the knee-bend of the left [hind] leg | δ Cru |

| 34 | ὁ ἐπὶ τοῦ βατραχίου τοῦ αὐτοῦ ποδός | The star on the frag of the hoof an the same leg | α Cru |

| 37 | ὁ ἐκτὸς ὑπὸ τὸν δεξιὸν ὀπισθόποδα | The star outside, under the right hind leg | μ Cru |

Transfer and Transformation of the Constellation

Mythology

The cross is actually an ancient instrument of torture and should therefore have no place in the sky. For Christians, however, the cross on which Jesus was nailed symbolises his resurrection and the redemption of all people from their sins. It is a sign of hope, symbolising a new beginning and the start of a better world.

The commonly assumed connection of the four points of the cross to the four cardinal virtues can be traced back far beyond Christianity; they are also found in many Greco-Roman philosophies, e.g. prominently in Plato.

Weblinks

References

- ↑ Filippo Camerota, »Columbus and Vespucci; Echos of the Commedia in oceanic navigation«, in: From Hell to the Empyreum, Dante’s World between Science and Poetry, hrsg. von Filippo Camerota, Exhibition Catalog: Museo Galileo, Florence 2021, S. 104-5.

- ↑ Amerigo Vespucci, Cronache epistolari, Lettere 1476-1508, hrsg. von Leandro Perini, Florenz 2013, S.92

- ↑ Ian Ridpath, Star Tales, Online Edition (Crux)

- ↑ Vita and Works of Dante Alighieri, provided by the Italian Dante Society https://www.danteonline.it/index.html

- ↑ Dante's Works online, provided by the Italian Dante Society: https://www.danteonline.it/opere/

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Dante's Comedia , provided by the Italian Dante Society

- ↑ Hoffmann, S.M. und Blume, D. (2023): „’l volger del ciel“ in Deutsches Dante-Jahrbuch: Dante und die Stadt. Kommunale Kultur und literarische Öffentlichkeit. Blume: “Dantes Sterne” (43-53), Hoffmann: “Planetarium Dantis” 1-42 (DOI 10.1515/dante-2023-0002), DeGruyter, 1-53